stomach

Eva Rudolf-Müller is a freelance writer in the medical team. She studied human medicine and newspaper sciences and has repeatedly worked in both areas - as a doctor in the clinic, as a reviewer, and as a medical journalist for various specialist journals. She is currently working in online journalism, where a wide range of medicine is offered to everyone.

More about the experts All content is checked by medical journalists.The stomach is part of the digestive tract, a sac-like enlargement between the esophagus and the duodenum. This is where the chemical digestion of food that began in the mouth continues. In addition, the prevailing acidic environment kills invading pathogens. Read everything you need to know about the stomach: anatomy, location, function, and common health problems!

What is the stomach

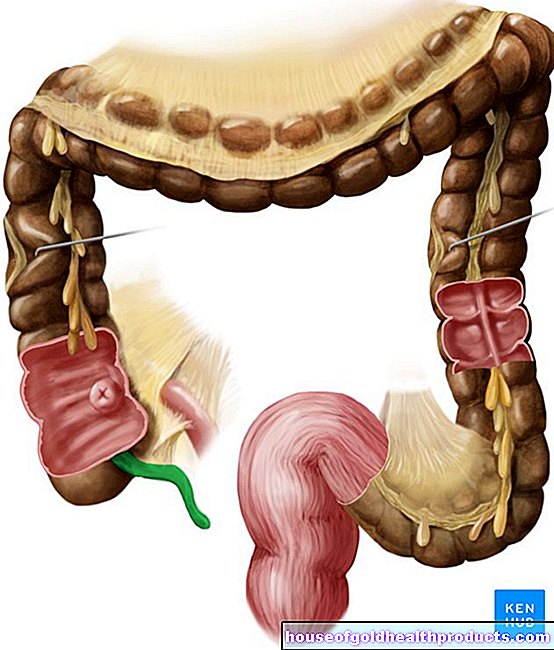

The stomach is a sac-like expansion of the digestive tract between the esophagus and the duodenum. It is divided into different areas: Above, at the entry point of the esophagus, lies the stomach mouth, called the cardia. To the left of this a dome-shaped section arches upwards, the base of the stomach or fundus. The main section of the organ, the stomach body or corpus, connects at the bottom. It goes into the stomach outlet (pylorus or gatekeeper), which is formed by a sphincter muscle.

This is how the stomach is built

The capacity of the stomach varies greatly: in an adult it is on average 2.5 liters, in a newborn it is 20 to 30 cubic centimeters. The size adapts to the lifestyle and eating habits: Those who always eat small meals usually have a smaller stomach than people who regularly consume large portions.

How long does food stay in the stomach?

Easily digestible foods such as fruit and vegetables stay around one to two hours, while difficult to digest, fatty foods around five to eight hours. Large amounts of food accelerate emptying into the small intestine.Liquids are released to the small intestine faster than semi-solid or solid food. Physical movement, standing and sitting lead to faster emptying, strong movements, on the other hand, inhibit the motor functions of the stomach wall as well as pain emanating from other organs.

What is the function of the stomach?

The stomach mixes the ingested food with the gastric juice to a well-mixed pulp. The gastric juice contains several important components:

- Digestive enzymes: pepsinogen or pepsin for protein digestion and lipases for fat digestion.

- Hydrochloric acid: converts the inactive precursor pepsinogen into active pepsin, creates the acidic environment that pepsin needs for its work and kills bacteria.

- Mucilages: protect the stomach wall from the aggressive hydrochloric acid and enzymes so that the organ does not digest itself.

- Intrinsic factor: protein that is then required in the intestine for the absorption of vitamin B12 into the blood.

The gastric juice is produced by the stomach wall and the glands in it (about two liters per day). These glands consist of different cell types: In the cardia area, secondary cells predominate, which produce the mucus. Main cells predominate in the body area, which also secrete mucus and also produce pepsinogen and the intrinsic factor. Parietal cells or parietal cells are particularly found in the fundus and corpus. They make hydrochloric acid, which lowers the pH of the stomach to two to three.

The inner wall of the stomach is covered with the protective layer of mucus. Underneath is a loose layer of connective tissue that is rich in blood vessels, nerves, lymph tissue and glands. This is followed by the muscle wall, consisting of three layers of smooth muscle, which mixes, chops and transports the food through its muscle tone. After the outer layer of the food has been digested, it is carried by wave-shaped contractions (peristalsis) to the pylorus (gatekeeper) and the next layer of food is mixed with the gastric juice. When all of the chyme is mixed, it is transported into the small intestine in again wave-shaped contractions and in portions. The gatekeeper opens and closes through chemical reactions in the duodenum.

Where is the stomach?

The stomach lies under the diaphragm, three quarters in the left upper abdomen (region hypochondriaca), and one fourth in the middle upper abdomen (region epigastrica). The lowest point is approximately at the level of the navel. When standing, the longitudinal axis of the stomach runs almost vertically - especially when it is full - and the lower end can then even lie under the pylorus. Air that is swallowed when eating collects when standing or when sitting upright at the top of the dome-shaped cardia.

What problems can the stomach cause?

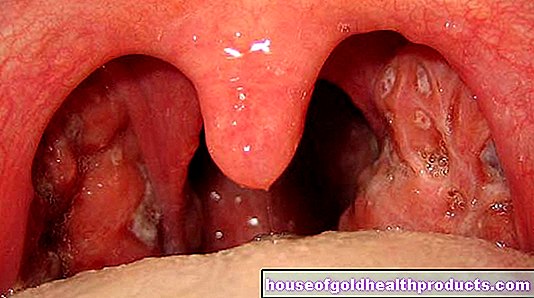

Inflammation and infection, as well as cancer, are the most common and occur at all ages. In the case of gastric mucosal inflammation (gastritis), the stomach acid attacks the layer of mucous membrane on the inner wall. Possible causes are medication, excess alcohol or nicotine, bacteria or viruses. Chronic gastritis can be caused by the bacterium Helicobacter pylori. If left untreated, ulcers will develop, which can lead to bleeding or even a gastric perforation.

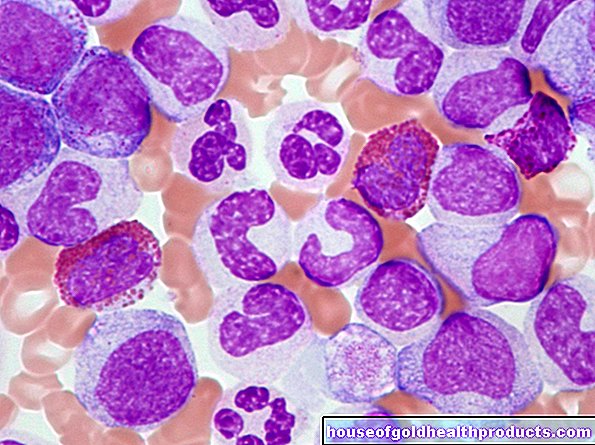

If the parietal cells are also affected in the event of damage to the mucous membrane (for example in the case of chronic gastritis), insufficient intrinsic factor may no longer be formed. As a result, enough vitamin B12 can no longer be absorbed - a vitamin B12 deficiency develops, which often leads to anemia, because the vitamin is important for blood formation. Neurological disorders can also occur because the vitamin is necessary to build up the protective covering around the nerves.

Heartburn occurs when aggressive acid rises from the stomach into the esophagus and irritates the mucous membrane there (reflux disease).

Tags: magazine book tip eyes