Mitral valve

Eva Rudolf-Müller is a freelance writer in the medical team. She studied human medicine and newspaper sciences and has repeatedly worked in both areas - as a doctor in the clinic, as a reviewer, and as a medical journalist for various specialist journals. She is currently working in online journalism, where a wide range of medicine is offered to everyone.

More about the experts All content is checked by medical journalists.The mitral valve is one of the four heart valves. It connects the left atrium with the left ventricle and acts as an inlet valve: The valve ensures that the blood only flows from the atrium into the ventricle and does not flow in the opposite direction. Read everything you need to know about the mitral valve!

Mitral valve: inlet valve in the left heart

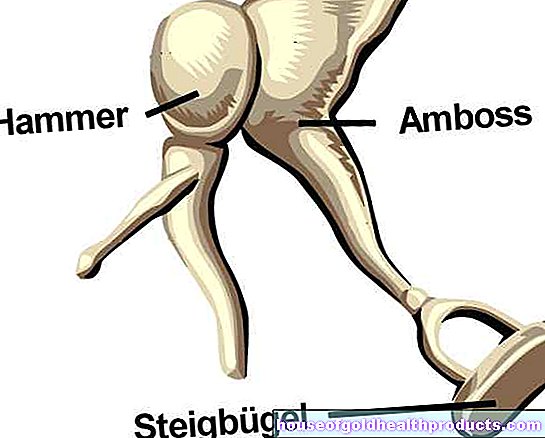

The blood passes through the mitral valve from the left atrium to the left ventricle. Due to its location, it belongs to the atrioventricular valves together with the tricuspid valve. Like the other three heart valves, it consists of a double layer of the inner lining of the heart (endocardium) and is a so-called leaflet valve. It has two "sails", a front and a rear, which is why it is also called the bicuspid valve (Latin: bi- = two, cuspis = spike, point).

The papillary muscles of the mitral valve

Sinewy strands attach to the edges of the cusps and connect them to the papillary muscles. These muscles are small protrusions of the heart chamber muscle into the ventricle. They prevent the freely hanging cusps of the mitral valve from beating back into the atrium as a result of the pressure generated during the contraction of the ventricle (contraction of the muscle in the systole).

Mitral valve function

As soon as the systole begins, the blood flow causes the free edges of the leaflets to cling tightly to one another, thus closing the border between the atrium and the ventricle. In addition to the heart muscle, the papillary muscles also tighten and hold the closed mitral valve in this position. As a result, the blood does not flow back into the left atrium, but takes its correct route through the aortic valve into the main artery and thus into the great bloodstream. In the following diastole (relaxation phase of the heart muscle), the blood flows from the atrium into the chamber. To do this, the mitral valve opens completely again. Incidentally, the mitral valve, like all heart valves, is attached to a fibrous ring of connective tissue in the heart skeleton.

Common mitral valve problems

In mitral stenosis, the mitral valve is narrowed, which means that the heart chamber no longer fills properly during diastole. In most cases, mitral valve stenosis is due to heart valve inflammation caused by rheumatic fever. It is seldom congenital or calcified purely through wear and tear and aging.

In mitral regurgitation, the mitral valve does not close tightly, so that blood from the heart chamber returns to the atrium during systole. As a result, a certain amount of blood "shuttles" back and forth between the atrium and the heart chamber. The causes of mitral valve insufficiency are, for example, bacterial endocarditis (heart valve inflammation), torn papillary muscles and tendons (e.g. in the case of a chest wall injury, surgery or a heart attack) or rheumatic diseases.

The doctor listens to valvular heart disease with a stethoscope. He perceives the mitral valve best in the area below the left nipple, between the fifth and sixth rib.

If one or both canopy cusps bulge into the atrium during systole, doctors speak of mitral valve prolapse. The flap can still be tight. More pronounced mitral valve prolapse also leads to valve insufficiency. The prolapse is partially congenital, but the cause is often unclear. It tends to affect women with weak connective tissue more often. Sometimes the doctor hears one or more "systolic clicks" with the stethoscope when the mitral valve prolapses.

Tags: healthy feet teenager foot care