Precious hours of freedom

Jens Richter is editor-in-chief at Since July 2020, the doctor and journalist has also been responsible as COO for business operations and the strategic development of

More posts by Jens Richter All content is checked by medical journalists.

Jaufenpass, Timmelsjoch, Penser Joch - Wolfgang Bornemann conquered the highest pass roads in the Alps on his own. In the bicycle saddle he can outsmart his illness. Wolfgang Bornemann suffers from Parkinson's

There are days when even the few meters to the garage cost a lot of strength and patience. In arduous triple steps, Wolfgang Bornemann then has to fight his way from the front door to his shiny silver touring bike. People with Parkinson's are sometimes frozen. Especially in the so-called off-phases they can hardly move, speaking is difficult, the facial features are frozen.

But when the 59-year-old gets on his bike and drives off, it seems as if the disease does not exist. As if he hadn't received the devastating diagnosis from his doctor 19 years ago. "All restrictions disappeared immediately on the bike," Bornemann told "I can pedal like everyone else, safely steer, brake, even speak." But only as long as it drives. "When I get off my bike, the symptoms are right back."

Disturbed fine-tuning

It took more than twelve years for Bornemann to discover the miraculous temporary healing. The observation gave him courage to upgrade the two-wheeler, which was only used sporadically in recent years, to a piece of sports equipment. The man from Lower Saxony gets on his bike three times a week and trains, covering between 2,000 and 3,000 kilometers every year. Bornemann has already explored half of Germany by bicycle, crossing the Alps almost every summer. In winter he switches to an ergometer - precious hours without "Parki", as he calls the disease. "I don't know why Parkinson's can't follow me into this niche."

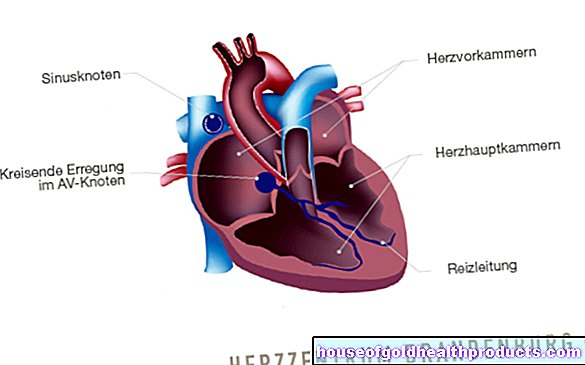

At 40, Wolfgang Bornemann was unusually young when the doctors diagnosed him with Parkinson's. Most patients only become ill after the age of 50, between seven and ten million people worldwide are affected, researchers estimate. In Parkinson's disease, the fine-tuning of voluntary movements no longer works properly. Nerve cells that produce the neurotransmitter dopamine die.

The so-called extrapyramidal system can then no longer properly coordinate the cooperation of the various muscle groups and the feedback coming from there. The treatment therefore aims primarily at this mechanism: the replacement of dopamine and greater sensitivity to the messenger substance. But what triggers the disease and why it affects some people so early is not known. Parkinson's research is still in its infancy.

Like rattling gears

The Dutch professor Bastiaan Bloem in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, is one of the leading Parkinson's researchers worldwide. One of his patients - a man with severely advanced Parkinson's who could hardly walk but cycled with no problems - amazed him a few years ago with a demonstration of his abilities.

Why do people with Parkinson's disease suddenly lose their symptoms on the bike - the halting, then exaggerated movements that are often reminiscent of the rattling gears of large, old machines? Why do the cramped muscles on the bike suddenly become soft, the movements round and fluid?

Bloem suspects that different parts of the brain are responsible for cycling than for walking. Exercise can also create new dopamine compounds in the brain, he found. At least that was the case in animal experiments. But can that alone explain why the cramped lower jaw loosens, the tongue becomes more flexible, and the language works again? Like with Wolfgang Bornemann?

Brain regions communicate again

Researchers in Cleveland (Ohio), USA, have now discovered something interesting: they used a special magnetic resonance imaging procedure to determine the oxygen consumption in the brains of their Parkinson's patients while they were pedaling on the ergometer. In doing so, they discovered that parts of the brain in the cerebral cortex (movement planning) and in the thalamus (movement control) that are important for performing movement again communicated more strongly with each other when their test subjects pedaled.

In Parkinson's disease, communication between these areas is interrupted. "But as soon as our patients were on their bikes, the cerebral cortex and thalamus began to better synchronize their activities again. We could see this from the identical rhythm in oxygen consumption," says study director Dr. Chintan Shah in a NetDoctor conversation. "The higher the patient's cadence, the stronger the effect."

The researchers also observed something else that gives rise to hope: the positive effects clearly outlived the training. Four weeks later, they were able to demonstrate improved communication between the motor cortex and the thalamus. "Even so, we still cannot say today whether cycling can slow down the course of the disease in the long term or even reverse it," says Shah. This is now to be shown by another study in which the patients train at home on ergometers for six months.

Dance on the vibrating plate

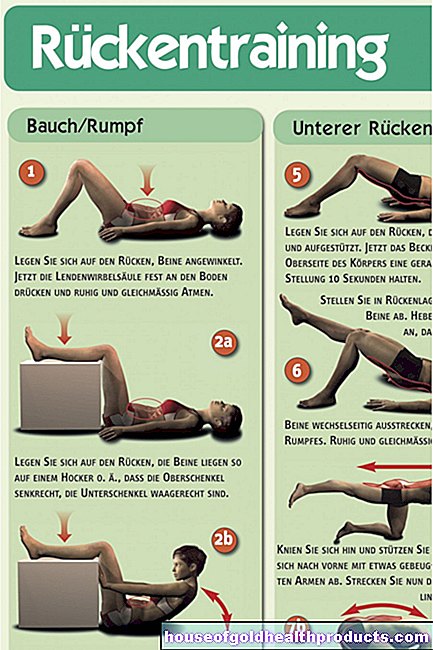

Cycling as therapy? Wolfgang Bornemann has also been the subject of scientific observations several times. Together with his friend Jürgen Weber, he climbed the 1,900 meter high pass road to the Hahntennjoch in summer 2010, Parkinson's researcher Bloem and Bavarian television accompanied them. The former IT specialist is currently working with his neurologist to test a device that alpine skiers in the national team can use to improve their balance: the so-called Zeptor.

The vibrating plate of the training device wobbles and dances irregularly on all levels, forcing the athlete balancing on it to make constant corrective movements - a very special challenge for the lazy motor skills of a Parkinson's patient. But "the thing works", Bornemann is convinced. "The device helped me to keep control of the bike even on the fast descents of the Alps." Or when it went so steeply uphill, despite all the effort, the pedals turned so slowly that the sporty 59-year-old and his "Parki" lurched across half the width of the street.

Search for new goals

Despite his fitness, which makes many younger sports colleagues' legs and lungs burn, Flachländer Bornemann wants to complete the alpine adventure and achieve his sporting successes with a little less risk in the future. "Parki leaves more and more traces on me too," says Bornemann. He therefore wants to find new roads and paths, new goals, and to keep cheating on the disease even after 20 years. "I don't know how I would be without the sport. But I can see that the sick people around me who don't do all of this are not doing as well as I am."

Tags: digital health palliative medicine Menstruation