Hip dysplasia

Martina Feichter studied biology with an elective subject pharmacy in Innsbruck and also immersed herself in the world of medicinal plants. From there it was not far to other medical topics that still captivate her to this day. She trained as a journalist at the Axel Springer Academy in Hamburg and has been working for since 2007 - first as an editor and since 2012 as a freelance writer.

More about the experts All content is checked by medical journalists.

Doctors refer to a congenital or acquired malformation of the acetabulum as hip dysplasia. It occurs in about two to three out of every 100 newborns, especially girls. If left untreated, hip dysplasia can lead to permanent damage to the femoral head or socket. A later handicap as well as premature signs of wear and tear are the possible consequences. Read everything you need to know about hip dysplasia here.

ICD codes for this disease: ICD codes are internationally recognized codes for medical diagnoses. They can be found, for example, in doctor's letters or on certificates of incapacity for work. Q65

Hip dysplasia: description

Hip dysplasia is a congenital or acquired malformation of the acetabulum. As a result, the still cartilaginous-soft femoral head of the thigh does not find a stable hold in the acetabulum. In the most severe case of hip dysplasia, hip dislocation, the head of the thigh bone slips out of the socket.

Hip dysplasia and hip dislocation can occur in only one hip joint or in both joints. In the case of a unilateral malformation, the right hip joint is affected much more often than the left.

Hip dysplasia: incidence

In every 100 newborns, two to three have hip dysplasia. A hip dislocation is much less common with a frequency of around 0.2 percent. Girls are more often affected than boys.

Hip dysplasia: adults

Hip dysplasia in babies that has not been recognized or is treated too late restricts mobility considerably in later life and can cause pain even in adolescents. There may be premature changes due to wear and tear, which limit the choice of occupation and can lead to early disability. Malformations of the hip joint such as hip dysplasia promote premature joint wear (osteoarthritis).

Hip dysplasia: symptoms

Hip dysplasia alone does not initially cause any symptoms. However, if it is not recognized in time, damage to the acetabulum and head (such as hip arthrosis in later life) or hip dislocation can result.

In the case of a hip dislocation, the femoral head (i.e. the head of the thigh bone) jumps out of the joint socket. In this case, the baby can only partially spread its legs. The leg on the affected side appears shorter than the other. The anal furrow and pubic fold are shifted towards the affected side. The shortening of the legs and the asymmetry of the folds can, however, be absent in the case of bilateral hip dislocation.

As a result of the hip dislocation, the "empty" joint socket can gradually deform. In some cases, the head of the thighbone can no longer be adjusted to its normal position.

In older children, hip dysplasia may result in a hollow back or a "waddling gait". If such symptoms occur, parents and their child should immediately consult a pediatrician or orthopedic surgeon.

Hip dysplasia: causes and risk factors

The exact causes of hip dysplasia are not known. But there are risk factors that favor the development of this malformation:

- Incorrect position of the fetus in the womb: Children born in breech or breech position are around 25 times more likely to have hip dysplasia than babies born in a normal birth position.

- Restricting conditions in the womb such as a multiple pregnancy

- Hormonal factors: The pregnancy hormone progesterone, which loosens the mother's pelvic ring in preparation for childbirth, presumably causes the hip joint capsule to loosen up in female fetuses - hip dysplasia can develop.

- Genetic predisposition: Other family members already had hip dysplasia.

- Malformations of the spine, legs and feet

- Neurological or muscular diseases such as open back (spina bifida)

- Poor posture of the hip joints after birth

Hip dysplasia: examinations and diagnosis

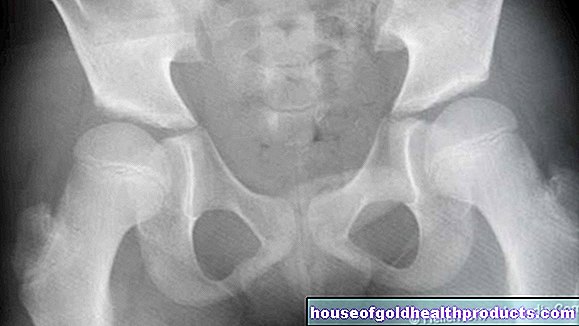

As part of the preventive examinations, the pediatrician routinely checks every child for hip dysplasia at U2 (third to tenth day of life). For a reliable diagnosis, he then carries out an ultrasound examination of the hip at U3 (in the 4th to 6th week of life). An X-ray examination to clarify hip dysplasia is usually unnecessary and also less reliable, as the still cartilaginous baby bones are less clearly visible in the X-ray than in the ultrasound.

On physical exam, the following signs may indicate hip dysplasia:

- Gluteal fold asymmetry (uneven skin folds at the base of the thigh)

- Splay inhibition (one leg cannot be splayed as far as usual)

- Unstable hip joint

Hip dysplasia: treatment

Treatment for hip dysplasia depends on the severity of the changes. Both conservative and operative measures are available.

Conservative treatment

The conservative treatment of hip dysplasia or hip dislocation consists of three pillars: maturation treatment, reduction and retention.

Maturation Treatment:

An instability in the hip joint at birth due to a delay in maturation resolves by itself within two months in 80 percent of cases with normal motor development. Ultrasound monitoring is usually sufficient as a medical measure. Maturation can be supported by changing the child's diaper with particularly wide diapers.

In the case of high-grade hip dysplasia, in which the femoral head is still in the socket, the baby is fitted with spreader pants or splint. The duration of treatment depends on the severity of the dysplasia and is continued until a normal acetabular cup is formed. This process is checked at regular intervals using ultrasound. In rare cases, the doctor will take an x-ray of the hip as soon as the acetabulum is mature at twelve months. He can check whether the femoral head and socket are well shaped.

Reduction and retention:

If the femoral head of a child with hip dysplasia has slipped out of the joint socket (dislocation), it must be "adjusted" into the socket (reduction) and then held (stabilized) there (retention). For children who are not older than nine months, a reduction bandage can be applied, in which the hip joints can spontaneously adjust when the child kicks in and the bandage then stabilizes them in this position for a longer period of time.

Another possibility is to manually straighten the “slipped” femoral head and then apply a cast in a sit-squat position for several weeks. It keeps the femoral head stable and permanent in the acetabulum. The re-established contact allows the head and socket to develop normally.

If the adjustment did not work or if the affected child is older, an extension treatment is often carried out in preparation. It is used to loosen the hip joint and stretch the shortened muscles.

surgery

If conservative measures to treat hip dysplasia are unsuccessful or if the malalignment is detected too late (in children three years of age or older, or in adolescents or adults), surgery is necessary. Various operative procedures are available for this.

Hip dysplasia: prevention

Hip dysplasia cannot be prevented. However, wide swaddling causes babies and toddlers to spread their legs more widely. This is considered beneficial for the hip joints.

For hip dysplasia to heal completely, it is crucial that it was detected early. A doctor should therefore examine babies for hip dysplasia at the U2 preventive examination, but at the latest at U3. A therapy started early reduces the risk of permanent damage to the femoral head or the joint socket.

Hip dysplasia: disease course and prognosis

The earlier hip dysplasia is treated, the faster it can be resolved and the greater the chances of recovery. With consistent treatment in the first weeks and months of life, the hip joints develop normally in over 90 percent of the children affected. If, on the other hand, hip dysplasia is diagnosed late, surgery can usually not be avoided. There is also a risk of hip dislocation and premature wear and tear of the hip joint, which can result in osteoarthritis in young adults.

The risks of an operation and reduction in size include, among other things, growth disorders of the femoral neck and so-called femoral head necrosis, i.e. the death of the femoral head.

However, if hip dysplasia is not treated, the joint socket will deform and later on it will become difficult to walk.

In the case of hip dysplasia, physiotherapy helps to counteract a limp. Above all, muscles that stabilize the hips are trained.

Tags: pregnancy therapies vaccinations

.jpg)