Carcinogens: got on the cow

Christiane Fux studied journalism and psychology in Hamburg. The experienced medical editor has been writing magazine articles, news and factual texts on all conceivable health topics since 2001. In addition to her work for, Christiane Fux is also active in prose. Her first crime novel was published in 2012, and she also writes, designs and publishes her own crime plays.

More posts by Christiane Fux All content is checked by medical journalists.Pathogens that research has long overlooked abound in the milk and serum of European cows. In an interview with, Nobel laureate Harald zur Hausen explains how they can cause cancer and how the infection can be slowed down in infancy.

In China, pork is traditionally mainly eaten. Beef, on the other hand, was rarely on the table, at least in the past. The idea of consuming smelly dairy products in the form of cheese was also found rather unsavory in the Middle Kingdom for a long time.

First came the cows, then came the cancer

However, around forty years ago, the Chinese began to introduce herds of European dairy cows. Above all, they wanted to improve the children's nutrition with the milk.

What nobody suspected at the time: there are pathogens in the milk and serum of European cattle that can cause cancer later in life. Decades later, cancer numbers began to rise in China. The same phenomenon was observed in India and Mongolia.

More steaks, more colon cancer?

In the case of colon cancer, the connection between beef consumption and the risk of disease has long been known. Less well documented, but quite likely, is that the risk of breast cancer and probably also prostate cancer from cow's milk products and beef increases. This is also shown by the example of the Asian countries.

It is neither viruses nor bacteria, nor fungi nor parasites that are responsible: “We are dealing with a completely new type of pathogen,” explains Prof. Harald zur Hausen in an interview with “Bovine Meat and Milk Factors”, or BMMF for short, is what his research group at the German Cancer Research Center in Heidelberg has named the cancer pathogens.

Chromosome rings with special abilities

These are ring-shaped structures of DNA, as often found in bacteria. The genome rings are not embedded in the main chromosome of the microbes, but lie outside of it in the plasma as mini-chromosomes. The DNA rings are therefore also called plasmids. They perform specialized tasks for the organisms - for example, they carry information that makes the bacterium resistant to antibiotics.

"Amazingly widespread"

“Basically, BMMF are plasmids that have become independent,” explains zur Hausen. They have changed their structure to such an extent that their genetic information can be read and reproduced in the cells of cattle and humans.

"They are astonishingly widespread among the population because they are relatively often ingested from cattle through dairy products and serum," says Zur Hausen. The latter reaches the human digestive tract via the blood in the meat of the animals as steak or goulash.

Free radicals in the tumor neighborhood

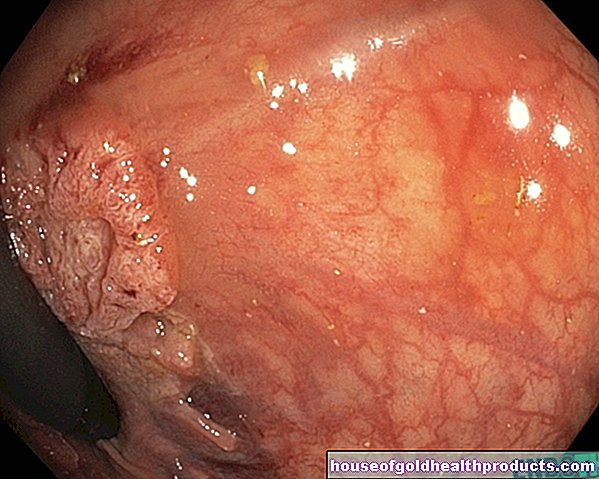

Scientists from zur Hausen's team led by Dr. Timo Bund has now been proven on the basis of tissue samples. To do this, the scientists first built artificial antibodies that attach to a specific protein (Rep). This, in turn, is what the BMMF need for their reproduction. By staining the antibodies, the cancer researchers were able to detect BMMF in 15 of 16 colon cancer tissue samples.

To their surprise, it turned out that it was not the cancer cells themselves that contained the Rep protein, but only the cells in the immediate vicinity of the tumors. A layer of connective tissue under the intestinal mucosa, the lamina propria, was particularly affected.

Inflammatory reactions as a cancer driver

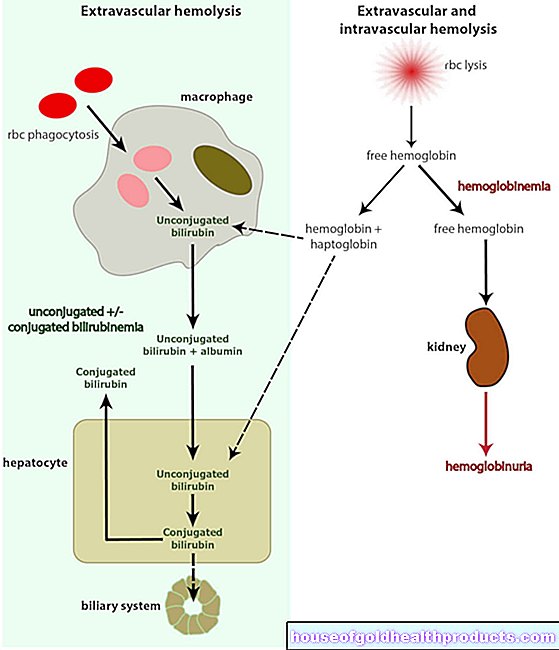

The absence of the pathogen in the cancer cells themselves suggests that the BMMF do not cause the cancer directly, but indirectly: They trigger choral inflammatory processes. This creates free radicals.

"Such highly reactive oxygen molecules promote the development of genetic changes," explains zur Hausen. The very reactive oxygen molecules act on the neighboring cells and cause mutations in the genetic material there, which can cause the cells to degenerate.

Mutations under the intestinal lining

The inflammation occurred mainly in the direct vicinity of the so-called intestinal crypts. These are tubular depressions in which the stem cells of the intestine sit. In order to regenerate the intestinal mucosa, they constantly produce large quantities of progenitor cells that divide quickly.

However, errors in the genetic material can occur with each division. However, under the harmful influence of free radicals, this is more common than usual - and this increases the risk of mutations occurring that cause the cells to degenerate.

The presence of certain phagocytes (macrophages) in the tumor environment is also typical of inflammatory processes. They have a specific binding molecule on their surface: CD68. "These immune cells are apparently supposed to suppress the acute inflammatory process somewhat," said Zur Hausen. But they are also likely to be attacked by BMMF.

Cattle pathogens in the tumor neighborhood

The researchers now compared samples from around intestinal tumors with intestinal samples from healthy people. They found that in samples from cancer patients, 7.3 percent of all intestinal cells in the tumor area had both Rep and CD68 proteins. In the intestinal cells of the healthy control group, it was significantly fewer at just 1.7 percent.

"We therefore consider the BMMF to be an indirect carcinogen, some of which will probably have an impact on the dividing cells of the intestinal mucosa for decades," says Zur Hausen.

Pathogens establish themselves with early contact

The infection with the pathogen occurs early: Most people are infected with the cattle pathogens in early childhood, namely after weaning. “During the breastfeeding period, the children receive special sugars in their breast milk, which apparently inhibit the absorption of such pathogens. That protects them from infection, ”said zur Hausen.

Mothers apparently also benefit from the protective effect of lactose - at least if they have several children: “It has long been well documented in the literature that women who breastfeed more than once are less likely to develop breast cancer,” reports the cancer researcher. The riddle surrounding the question of why this is so can be solved quite incidentally on the basis of these findings.

Long breastfeeding protects

But children who were breastfed for a year would only come into contact with cow's milk when their immune system is already mature. "Then the immune system can deal with such infections," explains the scientist. The children then developed antibodies that protected them from later infection. It cannot be ruled out entirely. But there is also no evidence that something like this happens more often.

"However, if children come into contact with cow's milk before their immune system is fully developed, the pathogens can implant themselves and cause chronic inflammation for life," says the researcher. What amounts of dairy products or beef they then consumed later probably no longer influences the risk of cancer later on.

Does heating protect against infection?

It is still unclear whether the method of preparation of cow's milk and beef plays a role in the infectivity. "We have no way of proving whether the pathogens are inactivated when they are heated," says zur Hausen.

The ring molecules are just as present in pasteurized milk as in unpasteurized milk. “But we don't know whether they can still penetrate the cells just as effectively,” says the researcher. However, he estimates the likelihood that heating milk and meat will have an effect.

Are there other unknown cancer pathogens slumbering in the body?

The group around zur Hausen suspects that there are many other pathogens that could cause other types of cancer. “We were able to sequence, identify and analyze data from around 120 potential pathogens.” So far, they have been waiting to be examined at the German Cancer Research Center.

More vaccinations against cancer?

This opens up great opportunities for cancer prevention: whether BMMF or other pathogens - a vaccination could offer reliable protection against the corresponding tumors. In the case of the “bovine milk and meat factor”, people might not even have to be vaccinated - it might be enough to immunize the cows and cattle.

Until then, people who can be proven to be infected with BMMF could be screened particularly closely for tumors.

The realization "only penetrates slowly"

But the professional world is apparently still not very open to the approach. Zur Hausen takes it calmly: "We have had the same experience with HPV," he reports on his work with the human papillomaviruses, which can cause cervical cancer. "Even then, the interest wasn't very great at first because nobody believed that such a connection could exist - something like this is getting through rather slowly."

In the end, the realization triumphed: In 2008 Harald zur Hausen received the Nobel Prize for Medicine for his discovery. More importantly, the HPV vaccine has been available for more than ten years to protect young girls from one of the most common forms of cancer in women.