Syncope (fainting)

Christiane Fux studied journalism and psychology in Hamburg. The experienced medical editor has been writing magazine articles, news and factual texts on all conceivable health topics since 2001. In addition to her work for, Christiane Fux is also active in prose. Her first crime novel was published in 2012, and she also writes, designs and publishes her own crime plays.

More posts by Christiane Fux All content is checked by medical journalists.Syncope is a brief period of fainting. The victim loses consciousness for a few seconds. Usually the cause is insufficient blood flow to the brain. The reason for this is often harmless. However, since a serious underlying disease can also be behind it, you should definitely have a syncope clarified by a doctor. Find out here what can trigger syncope, how you can give first aid if you faint and protect yourself from collapse.

Brief overview

- What is syncope? Brief fainting (duration: a few seconds). Also called circulatory collapse.

- First aid: elevation of the legs, supply of fresh air, if necessary stable lateral position, if breathing has stopped: resuscitation.

- Causes: short-term lack of oxygen in the brain, e.g. B. by nerve overreaction, getting up quickly from lying down, high pressure in the abdomen (sneezing, pressing on the toilet, etc.), varicose veins, diabetes, cardiac arrhythmias, medication

- When to the doctor Syncope is usually harmless, but should always be clarified by a doctor. There may be a disease behind it that should definitely be treated.

- Prevention: Avoid standing for long periods, stuffy rooms, stress, strong pressing (toilet), heavy lifting and heavy blowing of the nose. Compression stockings, regular endurance sport and enough drinking also help as a preventative measure. At the first signs of syncope, lie down and raise your legs!

What is syncope?

Syncope is a sudden, brief faint. In most cases syncope is harmless.

The cause is a sudden reduced blood flow in the brain - a circulatory collapse. The brain is very sensitive when it receives too little blood and thus too little oxygen: The person concerned then quickly loses consciousness. Once it is horizontal, more blood flows into the organ of thought: This is why one usually recovers quickly after a syncope.

Syncope is common. According to statistics, every second person has experienced a brief faint.

Other forms of acute unconsciousness

In addition to syncope, there are other forms of sudden loss of consciousness:

Mentally caused pseudosyncope

If someone passes out due to mental overload, doctors speak of pseudosyncope.

Some people suppress extreme emotional experiences, which then break out again on a physical level (this is referred to as a conversion disorder). Affected people can then fall into a state of unconsciousness, which - in contrast to a real syncope - usually lasts a few minutes. Occasionally it is accompanied by convulsive movements.

With syncope, those affected usually fall over with their eyes open. A pseudosyncope, on the other hand, generally takes place with the eyes closed.

Stroke and other vascular circulatory disorders

Even with a classic stroke, the brain does not receive enough oxygen. The reason is a blocked or burst vessel in the brain. Those affected collapse. Such a collapse lasts longer than syncope and often leaves permanent damage to the brain.

Blood sugar imbalance in diabetes

People with diabetes may lose consciousness if they have severe low blood sugar (hypoglycaemia) (hypoglycaemic crisis). If the sugar level is very high, there is a risk of a diabetic coma. In both cases, those affected need medical help quickly!

Absence in epilepsy

Some forms of epilepsy are also expressed in relatively brief fainting spells. Those affected are then no longer responsive and unresponsive for a few seconds during everyday activities. The gaze is often fixed, the eyeballs are twisted many times.

In contrast to syncope, these so-called absences have nothing to do with a circulatory breakdown, but their origin in the nerve cells (neurons) of the brain.

Syncope: first aid

Those who are about to faint usually no longer have time to help themselves. It is all the more important that people around you react correctly. So whenever you see someone pass out, here's what you should do:

- Lay the passed out on his back and elevate his legs. In many cases he will quickly regain consciousness because the blood supply to the brain is better when lying down.

- If you suspect that a heart attack could be the cause of fainting, straighten the person's upper body a little while lying down.

- After awakening, you should calm down the mostly confused and insecure patient.

- If the person concerned does not come to immediately, call the emergency doctor.

- Check that the patient is still breathing.

- If this is the case, place him on his side in a stable position.

- If you cannot find breathing, you must start resuscitation immediately.

The dangerous thing about unconsciousness is that the body's natural protective reflexes no longer work. This also includes the swallowing or coughing reflex. Vomit or blood in the mouth can therefore easily get into the airways. In addition, the muscles relax - in the supine position the tongue can sink backwards and block the airways. Both can be prevented with the stable side position.

Syncope: Here's how you can prevent it

You can do a lot yourself to prevent syncope. Here are some tips to keep in mind, especially if you pass out frequently:

- Try to avoid triggering factors. These include, for example, long periods of standing, long stays in warm and stuffy rooms, stress, but also alcohol.

- You shouldn't blow your nose too hard or push too hard when you have a bowel movement. Also avoid jerking heavy loads.

- With regular endurance sport and sufficient fluid intake, you can help stabilize your circulation. This can possibly prevent syncope.

- You can also stimulate your circulation with alternating baths according to Kneipp.

- Compression stockings help the blood flow back from the legs to the heart. This is an effective way of preventing syncope, especially in activities and professions that require long periods of standing.

Recognize harbingers and take countermeasures

Anyone who has already experienced syncope several times can often anticipate the next based on certain harbingers. These warning signs include acute dizziness, nausea, sudden sweating, "weak knees" and the famous blackening in front of your eyes. You may be able to avert the unconsciousness with a few tricks:

- Even a deep breath of fresh, cool air can get your circulation going again.

- Quickly lie on your back and elevate your legs. This often prevents the blood from sinking into your legs and with it syncope or at least a fall if you pass out.

- Do so-called isometric muscle exercises. In doing so, the vessels in the muscles are contracted so that the blood in them is pushed towards the heart. This works, for example, by crossing your legs, pressing them tightly together and at the same time tensing your leg, abdominal and gluteal muscles. Another exercise: hook your hands together and try to pull them apart vigorously.

- Sometimes even a sip of cold water helps to prevent impending syncope.

Syncope: causes and possible diseases

Doctors divide syncope into different categories depending on its causes:

Nervous system: vasovagal syncope

The vasovagal syncope (reflex syncope) is based on a dysregulation of the so-called autonomous (vegetative) nervous system. This nervous system, which cannot be voluntarily influenced, is divided into two parts: the sympathetic and the parasympathetic.

A vasovagal syncope occurs when the autonomic nervous system reflexively responds too violently to a stimulus (such as shock, cold, pain): The vessels are suddenly opened wide (by inhibiting the sympathetic nervous system), causing the blood to "sink" in the legs, and / or the heartbeat slows down or stops briefly (mediated by the vagus nerve, which is part of the parasympathetic nervous system). The result in all cases: The brain briefly receives too little blood (and therefore oxygen), so that the person affected passes out.

Possible triggers for vasovagal syncope are:

Overreaction of the vagus nerve

Pain, shock, fear, extreme cold or heat, psychological stress, long periods of standing and even noise can provoke an overreaction of the vagus nerve (nervus vagus). Among other things, this regulates the heartbeat.

Fainting can also occur if strong pressure is built up in the abdomen or chest (e.g. when defecating or blowing your nose violently). In such cases, syncope is harmless and usually only occurs sporadically. In some people, however, the autonomic nervous system seems to be particularly sensitive. Then it can often lead to a small circulatory collapse.

Disorder of the autonomic nervous system

Vagal syncope can also be caused by a fundamental disorder of the autonomic nervous system. Doctors then speak of an autonomic neuropathy. This can express itself through various symptoms, including syncope.

Carotid sinus syndrome

In people who suffer from the so-called carotid sinus syndrome, the carotid artery is overly sensitive to pressure.

The carotid artery is equipped with receptors that report to the brain when the blood pressure is too high. The brain then uses the autonomic nervous system to ensure that the vessels dilate and the heartbeat slows down - blood pressure drops.

In people with carotid sinus syndrome, these receptors are overly sensitive. Sometimes a touch on the neck (e.g. when shaving) or strong turning of the head is enough for the vessels to suddenly widen and the blood pressure to drop. Syncope may then occur because the brain is not supplied with enough blood.

This type of syncope is rare in younger people. In the elderly, however, it is not uncommon.

Circulatory system: orthostatic syncope

Orthostatic syncope can occur when someone quickly gets up from a lying position. The blood, which was evenly distributed over the body when lying down, sinks into the lower half of the body following gravity. The brain then briefly receives too little blood, which triggers the syncope.

Usually getting up quickly from a lying position is not a problem. Orthostatic syncope only occurs when the function of the so-called sympathetic nervous system is disturbed. In the autonomic nervous system, this important nerve network acts as an antagonist to the parasympathetic nervous system. While the vagus nerve (as part of the parasympathetic nerve) dilates the vessels, the sympathetic nerves can constrict the vessels and thus restrict blood flow.

When getting up quickly from a lying position, the sympathetic nervous system normally prevents the blood from sinking into the legs - it reflexively triggers a narrowing of the vessels. However, this mechanism does not work reliably with orthostatic syncope.

Several factors can favor orthostatic syncope:

- Insufficient fluid: If, for example, the circulating blood volume is reduced due to a major lack of fluid, the sagging in the lower half of the body is more noticeable when standing up. The risk of syncope is then higher.

- Varicose veins: Varicose veins are pathologically enlarged veins on the surface of the skin. On the legs, they sometimes act like an additional reservoir of fluid. As a result, a larger volume of blood sinks into the legs of those affected when they stand up from lying down. This can provoke orthostatic syncope.

- Nerve damage in diabetes: The high blood sugar levels in diabetes can damage the nerves over time. Such diabetic polyneuropathy can also affect the autonomic nervous system. In some patients, the reflex-induced contraction of the vessels when getting up from lying down takes place too slowly - they pass out.

Heart: cardiac syncope

Cardiac arrhythmias can impair the blood and therefore oxygen supply to the brain to such an extent that syncope occurs. For example, if the heart beats too slowly (bradycardia) or too fast (tachycardia), it no longer pumps enough blood into the circulation. As a result, the brain does not get enough oxygen for a short time. The possible consequence is a circulatory collapse.

Other diseases can also promote syncope by causing the heart to pump too little blood volume into the circulation with each contraction. This can be the case, for example, with a narrowing of the aortic valve (aortic valve stenosis). The same applies to a pathological thickening of the heart muscle (hypertrophic cardiomyopathy). Fainting can also occur in the event of a heart attack.

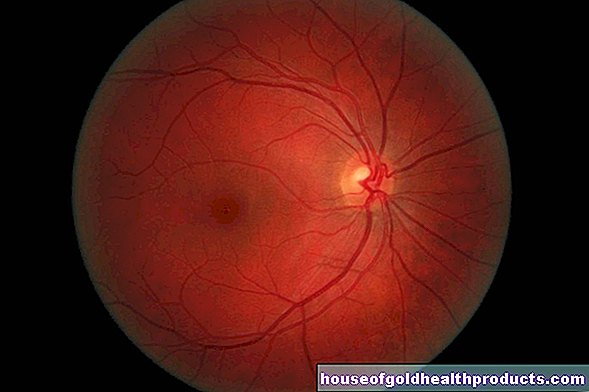

Brain: cerebrovascular syncope

This fourth large group of syncope describes so-called tap phenomena, also known as steal syndromes.

One example is subclavian steal syndrome. It occurs when the subclavian artery is narrowed. Then the arm muscles that are supplied by this artery will not receive enough blood. To compensate for this, the clavicle artery taps into the vertebral artery (arteria vertebralis), which carries blood to the brain. In principle, the collarbone artery “steals” blood from the vertebral artery and thus from the brain. The latter then receives less blood. Those affected can faint more often than not.

Medication

Certain drugs can also trigger syncope. These include those against high blood pressure, depression or cardiac arrhythmias. If you take such preparations and faint more often, you should talk to your doctor. He may be able to prescribe you a different drug that is less likely to affect your circulation.

Syncope: treatment

Syncope is one of the most common reasons people come to the emergency room. No wonder - suddenly losing consciousness can be quite unsettling.

An examination in the hospital is sensible and advisable. There they can clarify whether the syncope has a serious cause that needs to be treated.

Syncope: The doctor does that

What treatment the doctor will give will depend on the cause of the syncope. The reasons for the brief loss of consciousness should still be clarified by the emergency doctor or in the emergency room.

Usually a patient interview (anamnesis) helps the doctor to identify possible causes.

If cardiac arrhythmias are suspected, the patient's cardiac activity is monitored and monitored for some time via a monitor. If the suspicion is confirmed, the doctor will suggest suitable treatment if necessary (e.g. with medication).

In the case of circulatory dysfunction (orthostatic syncope), otherwise healthy people usually do not need specific therapy. If syncope occurs more frequently, the doctor can prescribe medication for it.

Syncope: when is it dangerous?

Even if syncope is usually harmless and / or at least not an emergency, if someone tips over, they can fall dangerously or cause an accident (such as fainting while cycling or driving a car). Fortunately, this rarely happens.

Cardiac syncope is probably the most dangerous variant.The underlying heart problems can be potentially life threatening. This is especially true if they are not discovered and treated in good time.

If syncope occurs together with pain or a feeling of pressure in the chest, you should call an emergency doctor. It may be a heart attack.

Even with syncope in connection with pale, cold sweaty skin and bluish lips, those affected belong in the emergency room. Symptoms can indicate shock and serious lack of oxygen.

Tags: Baby Child smoking Menstruation

.jpg)