Vulvar cancer

Martina Feichter studied biology with an elective subject pharmacy in Innsbruck and also immersed herself in the world of medicinal plants. From there it was not far to other medical topics that still captivate her to this day. She trained as a journalist at the Axel Springer Academy in Hamburg and has been working for since 2007 - first as an editor and since 2012 as a freelance writer.

More about the experts All content is checked by medical journalists.

Vulvar cancer is a malignant tumor of the external genital organs in women. The condition is rare and affects mostly older women. For some years now, however, increasingly younger people have also been suffering from it. Read everything you need to know about the topic here: How can you recognize a vulvar carcinoma? What causes the malignant tumor? How is he treated? What are the chances of recovery from vulvar cancer?

ICD codes for this disease: ICD codes are internationally recognized codes for medical diagnoses. They can be found, for example, in doctor's letters or on certificates of incapacity for work. C51

Brief overview

- What is vulvar cancer? Malignant disease of the external genital organs in women. Usually arises from skin cells and only rarely from other parts of the female pubic area (e.g. the clitoris).

- How common is vulvar cancer? Vulvar cancer is rare. In 2017 there were around 3,300 new cases in Germany, with an average age of 73 years. However, younger women are also becoming increasingly ill.

- How do you recognize vulvar cancer? The first signs are non-specific (such as itching, pain, small skin lesions). Later, a visible lump appears that grows faster and faster and sometimes bleeds. Possibly also discharge with an unpleasant smell.

- What does the treatment look like? Surgical removal if possible; in addition or as an alternative, radiation therapy and / or chemotherapy.

- Can vulvar cancer be curable? Vulvar cancer in its early stages has a good chance of recovery. However, these decrease very quickly when the lymph nodes are infected. If other organs are affected, vulvar cancer is considered incurable.

Vulvar cancer: symptoms

The symptoms of vulvar cancer in the early stages are very unspecific - many affected women therefore do not even think of a serious disease such as vulvar cancer. The first signs that may appear are:

- persistent itching in the vulva

- Pain, either spontaneously or, for example, when urinating (dysuria) or during sexual intercourse

- Burning sensation in the vulvar region

- Vaginal bleeding or discharge

- Skin / mucous membrane lesions in the vulva area, e.g. small, reddish, slightly raised spots or white, thickened indurations or weeping, non-bleeding small erosions

Sometimes persistent itching is the only early-stage sign of vulvar cancer. There are also many women who have no symptoms at all in this early tumor stage.

As the disease progresses, a tumor becomes visible, for example as a noticeable lump or as an ulcer that looks like a cauliflower. It grows slowly at first, later faster and faster and can also bleed.

Other possible symptoms of vulvar cancer in advanced stages are increasing pain and an unpleasant smelling discharge. The latter is caused by dying tumor cells that are broken down by bacteria.

Where does vulvar cancer develop?

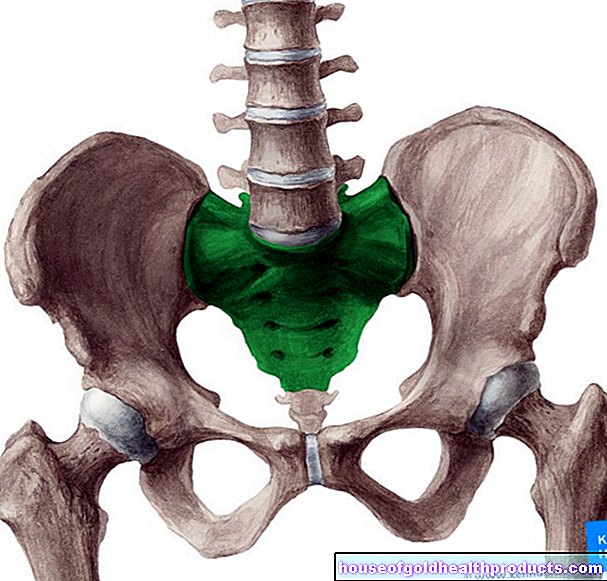

In principle, a malignant tumor can develop anywhere in the vulvar area. For some years now, most vulvar cancers have been localized in the anterior region of the vulva, i.e. in the area of the labia minora, between the clitoris and urethra or directly on the clitoris. In the remaining cases, the tumor arises in the posterior vulvar region, approximately to the side of the large labia, at the posterior vaginal entrance or on the perineum (perineum = area between the external genital organs and the anus).

If the vulvar cancer develops on the inside of one labia, a daughter tumor can form over time through direct contact with the opposite labia. Doctors then speak of a set-off metastasis.

Vulvar Cancer: Chances of a Cure

Several factors influence the prognosis of vulvar cancer. The most important thing is how big the tumor is, how deep it has penetrated the underlying tissue and to what extent it has already spread.

Vulvar cancer & survival rate: that's what the statistics say

For vulvar cancer, the relative 5-year survival rate is 71 percent, which means: In 71 percent of women affected, the malignant tumor did not lead to death five years after diagnosis (sources: Center for Cancer Registry Data and Vulvar Cancer Guideline).

This information relates to diseases across all stages. If one looks at the prognoses in the different tumor stages, the same applies as with other cancers: the earlier treatment is given, the sooner vulvar cancer can be cured.

In fact, in most cases (around 60 percent), vulvar cancer is discovered at an early stage (stage I). The vast majority of women affected can then be cured. As soon as the cancer has spread to lymph nodes in the groin and possibly also in the small pelvis, the prognosis deteriorates very quickly. If other organs (such as the lungs, liver, bones, brain) are already affected by cancer, vulvar cancer is considered incurable.

The prognosis may differ in individual cases

As informative as statistical data can be, one should not forget: Whether or not a woman will die of a diagnosed vulvar cancer also depends on individual factors - the probability of survival in individual cases can therefore differ from the statistical survival rate.

Vulvar Cancer: Causes & Risk Factors

Vulvar cancer occurs when cells in the pubic area degenerate and begin to multiply in an uncontrolled manner. Depending on which cells these are, a distinction is made between different types of vulvar cancer:

In around nine out of ten cases, cells of the top layer of skin or mucous membrane (squamous epithelium) in the vulva degenerate - then vulvar cancer is a so-called squamous cell carcinoma, i.e. a form of white skin cancer. The tumor usually forms a horny layer on the surface (keratinized squamous cell carcinoma), but can also remain keratinized (non-keratinized squamous cell carcinoma).

The most common form of vulvar cancer - keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma - usually develops independently of an infection with human papillomavirus (HPV; see risk factors) and is preferred in older women. The second most common are non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinomas, which are more likely to be HPV-dependent and mostly affect younger women (mean age: 55 years).

More rarely, vulvar cancer develops from cells other than the squamous epithelium. Basal cell carcinoma of the vulva can develop from the basal cell layer of the skin or mucous membrane - the second form of white skin cancer. Pigment-forming skin cells (melanocytes) in the pubic area can lead to degeneration of black skin cancer (Mailgne's melanoma). Other forms of vulvar cancer, such as adenocarcinoma that develops from the atrial glands (Bartholin's glands) at the entrance to the vagina, are very rare.

Causes unclear

Whether squamous epithelium, basal cell layer or Bartholin's glands - so far it is not known exactly why cells in the vulva area suddenly degenerate in some women and lead to vulvar cancer. As with other cancers, it is very likely that a number of factors interacting is necessary for tumor development.

Risk factors for vulvar cancer

These risk factors include the so-called vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN). This refers to cell changes in the uppermost cell layer (epithelium) of the vulva. They can become precancerous (precancerous). Doctors differentiate between three VIN stages:

- VIN I: Slight tissue changes that are limited to the lower third of the vulvar epithelium.

- VIN II: Moderate tissue changes affecting the lower two thirds of the vulvar epithelium.

- VIN III: Severe tissue changes that affect the entire vulvar epithelium.

Stage VIN I is not considered to be a precancerous stage, but in most cases regresses. VIN II and VIN III, on the other hand, can develop into vulvar cancer over the course of a few years.

A special form of VIN is Paget's disease of the vulva, a malignant tissue change that originates from the skin appendage glands. It is also considered a precursor to vulvar cancer.

The development of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasms (VIN) is almost always related to a chronic infection with human papillomavirus (HPV). Some types of these viruses (e.g. HPV 16) can trigger the formation of cancer precursors. Persistent infection with such viruses is therefore also an important risk factor for vulvar cancer.

The same applies to other cancers (or precancerous stages) in the genital or anal area, the development of which can also be related to human papilloma viruses. These include vaginal cancer, cervical cancer and anal cancer.

The fact that persistent immune deficiency can also lead to vulvar cancer is usually also related to HPV: if the immune system is permanently weakened, for example due to an HIV infection or the use of immunosuppressive drugs (after organ transplantation or autoimmune diseases), chronic HPV can develop more easily -Develop infection, which in turn favors the development of vulvar cancer.

In addition to HPV, some other sexually transmitted pathogens can also contribute to the development of vulvar cancer - herpes viruses (genital herpes), chlamydia and the causative agents of syphilis.

Also independent of an HPV infection, autoimmune-related processes such as the chronic inflammatory skin disease lichen sclerosus can increase the risk of vulvar cancer - more precisely for the most common form of vulvar cancer, keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva, which occurs mainly in older women.

Smoking is another risk factor for vulvar cancer. Age also plays a role: As mentioned at the beginning, vulvar cancer is primarily a disease of older women, although younger women are now increasingly developing it as well.

Incorrect genital hygiene is also considered unfavorable: a lack of hygiene in the genital area can be just as harmful as the frequent use of vaginal lotions or intimate sprays.

Vulvar Cancer: Examinations & Diagnosis

The right contact person for suspected vulvar cancer is the gynecologist. He can use various tests to determine whether a woman actually has a malignant vulvar tumor:

>> Inspection and scanning

As part of a comprehensive gynecological examination, the doctor will first carefully inspect the vulva, the vagina and the cervix - pathological tissue changes often occur in several places. During the inspection, the doctor pays attention to the coloring of the skin and any abnormalities in the tissue such as spots, cracks, thickening, flaking or ulcers.

In addition, the species scans the entire genital area. He pays attention to any knots or thickening in the tissue. The lymph nodes in the groin are also included in the palpation examination. If they are enlarged and / or painful, this can indicate an infestation with cancer cells, but there are also many other reasons.

>> Colposcopy

The doctor can examine suspicious tissue areas more precisely using a colposcopy. He uses a special magnifying glass with 10 to 20 times magnification (colposcope).

In order to better assess the suspicious areas, the doctor can carry out the acetic acid test: He dabs a very diluted acetic acid solution on the areas with a cotton ball. Healthy tissue does not respond to this with a change in color, while changed cells usually turn whitish (leukoplakia) - a possible indication of cancer.

Attention: In contrast to VIN lesions, Paget's disease of the vulva does not show a white color in the acetic acid sample!

>> biopsy

The doctor takes one or more tissue samples (biopsy) from every unclear tissue change - either as a punch biopsy or as an excisional biopsy:

In a punch biopsy, a cylinder of tissue is punched out of the suspicious area with the help of a special instrument. (e.g. a punch). During an excisional biopsy, the entire suspicious area is cut out (e.g. in the case of pigmented lesions, which may be black skin cancer).

The histological (histological) examination of the samples in the laboratory can finally clarify whether it is cancer or a precancerous stage.

The tissue is usually removed under local anesthesia. The doctor can close the wound with a suture.

Further examinations in confirmed vulvar cancer

Once the diagnosis of vulvar cancer has been made, the doctor will order various further examinations depending on the individual case. These include the following examinations:

A comprehensive gynecological examination of the entire genital and anal region helps to determine the tumor size and location more precisely.

The doctor uses a rectal examination to scan the rectum with a finger to look for signs of cancer. If there is a corresponding suspicion, an endoscopic examination of the rectum - rectoscopy (rectoscopy) - can provide certainty.

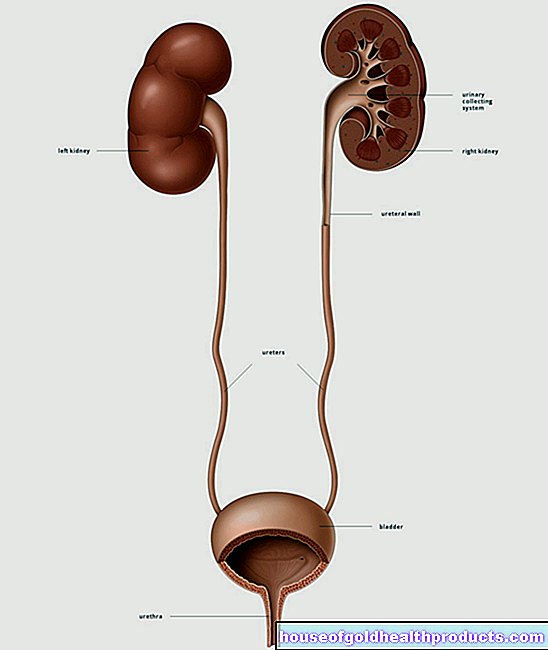

The urinary tract can also be examined endoscopically (urethrocystoscopy) if an infection with cancer cells is suspected.

Ultrasound examinations of the vagina, groin, pelvic organs and liver can also provide information about the spread of the tumor.

If lung metastases are suspected, chest x-rays can be made. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provide even more detailed images of the inside of the body and thus more precise evidence of metastases.

Division into disease stages

On the basis of all the test results, vulvar cancer can be assigned to a certain stage of the disease. This is important for therapy planning.

The stages of vulvar cancer according to the so-called FIGO classification (FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d "Obstétrique) are:

- Stage I: Vulvar cancer, which is limited to the vulva or the vulva and the perineum (perineum = area between the external genital and anus). No lymph node involvement. Depending on the maximum extent of the tumor and the depth of its penetration into the tissue, a distinction is made between stage Ia and stage IB.

- Stage II: tumor of any size that has spread to the lower third of the vagina and / or urethra and / or anus. No lymph node involvement.

- Stage III: tumor of any size that has spread to the lower third of the vagina and / or urethra and / or anus. Additionally involvement of lymph nodes in the groin. Depending on the extent of the lymph node involvement, a distinction is made between stage IIIA, stage IIIB, and stage IIIC.

- Stage IV: tumor of any size that has spread to the upper two-thirds of the vagina and / or urethra and / or the anus and / or the mucous membrane of the urinary bladder or rectum, or that is fixed to the pelvic bone (stage IVA) or has formed distant metastases (stage IVB).

Vulvar cancer: treatment

How medical professionals treat vulvar cancer depends largely on the type, stage and location of the tumor. The general state of health of the patient and her age are also taken into account (relevant with regard to family planning and maintenance of sexual function).

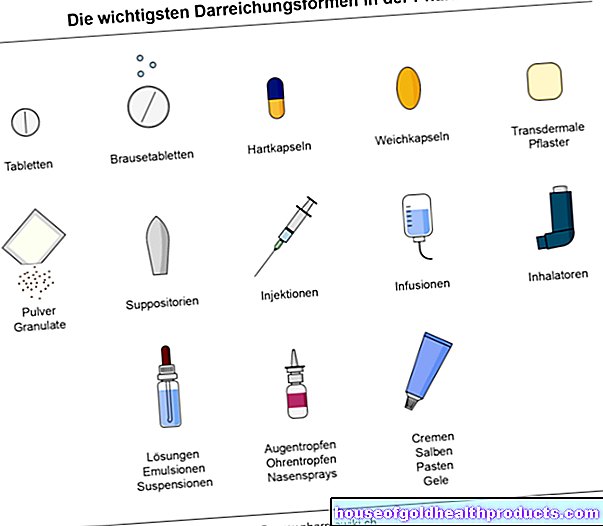

Basically, the options for treating vulvar cancer are surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy. They can be used individually or in different combinations - individually adapted to the patient.

surgery

The treatment of choice for vulvar cancer is surgery: If possible, one always tries to cut out the tumor completely while preserving the vulva as far as possible. Surgery is only avoided in exceptional cases, for example if a woman cannot be operated on for health reasons or the tumor has already spread to the anus.

How extensive the operation has to be depends on the stage of the disease:

>> Small tumor: If the tumor is still very small and not yet penetrated very deeply into the skin, it is usually sufficient to cut it out together with a border of healthy tissue. If necessary, the surgeon also removes the lymph nodes in the groin. Or he initially only cuts out the sentinel lymph nodes - the first inguinal lymph nodes located in the outflow area of the tumor. If tissue tests show that they are free of cancer cells, the remaining lymph nodes in the groin do not need to be removed.

>> Larger tumor or multiple tumor sites: For tumors that are already larger, have already spread to neighboring structures (such as the urethra, clitoris, vagina) or occur in several places, more extensive surgery is required. Not only will the cancerous tissue itself be removed with a margin of healthy tissue, but also part or all of the vulva (along with the underlying fatty tissue). The removal of the vulva is called a vulvectomy.

As part of this procedure, the lymph nodes in the groin are always removed because there is a high risk that they will also be affected by cancer. If tissue tests confirm this, the pelvic lymph nodes must also be excised.

Surgery risks

In the case of small tumors in the vicinity of the clitoris or the urethra, in particular, surgery is usually carried out with the smallest possible margin to healthy tissue in order to protect the clitoris and urethra. However, if too little healthy tissue is cut out at the edge, the tumor can return.

When the vulva is completely removed, about every second patient has to struggle with wound healing disorders afterwards. Other possible consequences of the radical intervention are, for example, sensory disturbances, scarring, constrictions, urine loss and recurring urinary tract infections.

Considerable risks are also to be expected when removing all lymph nodes in the groin or the pelvis. Affected women very often suffer from recurring lymph accumulations, lymphedema in the legs and inflammation.

radiotherapy

If lymph nodes in the groin or in the pelvis are affected by cancer, these areas are irradiated. Vulvar cancers themselves generally do not respond particularly well to radiation therapy. Nonetheless, this treatment method can be helpful in the following cases:

- In addition to an operation: Adjuvant radiation therapy is carried out after an operation, for example if the tumor could not be removed completely or not with a sufficiently large margin. A neoadjuvant radiation therapy precedes the operation - it is intended to reduce a tumor that is inoperable due to its size or location (e.g. close to the rectum) to such an extent that surgical removal is possible.

- Instead of an operation: There are also vulvar carcinomas that cannot be operated on and are only irradiated (definitive irradiation).

To make radiation therapy more effective, it can be combined with chemotherapy. Doctors refer to this as radiochemotherapy.

chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is also not very effective in vulvar cancer. That is why it is usually combined with other therapies, such as radiochemotherapy (as an alternative or in addition to surgery). Chemotherapy is mainly used for cancer of the vulva, which has already formed daughter settlements in more distant regions of the body (distant metastases).

Supportive therapy

This includes therapeutic measures that are intended to prevent or reduce therapy or tumor-related symptoms. Some examples:

Antiemetic drugs are given to combat nausea and vomiting - possible side effects of radiation and chemotherapy. Diarrhea as a result of radiation or chemotherapy can also be treated with medication.

Radiation therapy in the urogenital area can trigger acute cystitis. Then, for example, anticonvulsant and pain reliever medication and, if necessary, antibiotics help.

Cancer patients often suffer from anemia - either caused by the tumor itself or by tumor therapy. The doctor may, for example, give blood transfusions for treatment.

Cure is no longer possible for end-stage vulvar cancer. Therapeutic measures such as surgery, (radio) chemotherapy or the administration of pain medication rather aim to alleviate the patient's symptoms in order to improve her quality of life.

Vulvar cancer: prevention

Some of the vulvar cancer cases arise in connection with a chronic HPV infection. So if you prevent infection with human papillomavirus, you prevent VIN lesions as possible precursors of vulvar cancer. Avoiding such an infection is not easy because the viruses are widespread. Recommended measures include proper hygiene and the use of condoms if you change sexual partners more often - and in certain cases vaccination against HPV:

The vaccination is recommended for all girls and boys between nine and 14 years of age, preferably before the first sexual intercourse, because you get infected very quickly during sex. Missed vaccinations should be made up at the latest by the age of 18. In individual cases, the HPV vaccination can also be useful at a later point in time - interested parties should discuss this with their doctor (e.g. gynecologist).

The HPV vaccination offers protection against infection with high-risk HPV types - virus types that are associated with an increased risk of cancer. This primarily affects cervical cancer, but also, for example, penile cancer, vaginal cancer, anal cancer and vulvar cancer.

It is also important to identify and treat (possible) precancerous stages at an early stage, including above all vulvar intraepithelial neoplasms (VIN): These tissue changes in the pubic area have increased in recent decades, especially in women between the ages of 30 and 40. The stages VIN II and VIN III are critical: in 15 to 22 percent of cases they develop into vulvar cancer over a mean period of three to four years.

Tags: baby toddler palliative medicine unfulfilled wish to have children