"Medicine is like a thriller"

Dr. Andrea Bannert has been with since 2013. The doctor of biology and medicine editor initially carried out research in microbiology and is the team's expert on the tiny things: bacteria, viruses, molecules and genes. She also works as a freelancer for Bayerischer Rundfunk and various science magazines and writes fantasy novels and children's stories.

More about the experts All content is checked by medical journalists.In the “Center for Undetected Diseases” in Marburg, doctors get to the bottom of puzzling symptoms. What the US television series Dr. House has something to do with it, reveals Professor Jürgen Schäfer in the interview.

Prof. Jürgen Schäfer

Prof Jürgen Schäfer, born in 1956, became known worldwide as the German "Dr. House". Following the example of the US television series, he has been clarifying difficult medical cases at the Center for Undetected and Rare Diseases in Marburg since 2008. He completed his habilitation in internal medicine and is Academic Director of the Phillips University in Marburg.

Mr. Schäfer, patients who come to you suffer from inexplicable diseases. Is your job mainly detective work?

Yes, medicine is like a thriller - sometimes you have to search for “the culprit” for a long time on the basis of circumstantial evidence. To do this, we make a completely normal differential diagnosis, i.e. in the case of diseases with similar symptoms, we check which is the most likely cause.

"If we have to rule out the probable, the improbable must be the truth," said Sherlock Holmes.

It is exactly like that.

Why are you particularly good at helping in puzzling cases at the “Center for Undetected Diseases”?

We hold team meetings in which doctors from all disciplines sit at one table: heart specialists, pulmonologists, psychosomatists, cancer specialists, neurologists, radiologists, general practitioners and so on. There we discuss complex cases from different perspectives. The dynamism that arises is not only really fun, but also brings ideas and considerations into play that you would hardly have come up with on your own. Still, we are no better medical professionals than others. In principle, every university hospital with all the different disciplines represented there is predestined for such problem cases.

The story of starting your Center for Undetected Diseases is a curious one.

We didn't found the center entirely voluntarily - it was actually the television series “Dr. House ". There, too, a doctor tracks down the causes of inexplicable symptoms. I have been giving a seminar for six years, that is, “Dr. House - Revisited ”. I watch the first minute of a Dr. House episode. And then we think about what the patient dropping dead or spitting blood might have. Then the next clip continues and we discuss what the TV colleagues are doing and what we would do in real life. Overall, the cases in the series are very well researched. This somewhat unusual seminar was reported in the press. As a result, many desperate patients sent us their papers.

How many inquiries do you have on the table?

In the beginning there were only two or three inquiries a week - I was able to do that on the side. But then at some point I got ten letters a day. There was only the option of sending these mailings back to the sender with a note "unopened due to overloading" or setting up an appropriate structure in order to deal with the onslaught to some extent. Together with the management, we then decided on the latter.

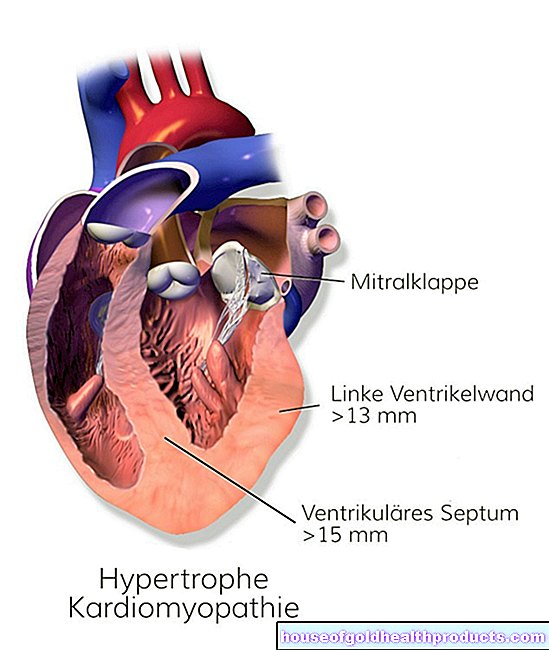

You saved the life of a patient because of a similar case in a Dr. House episode.

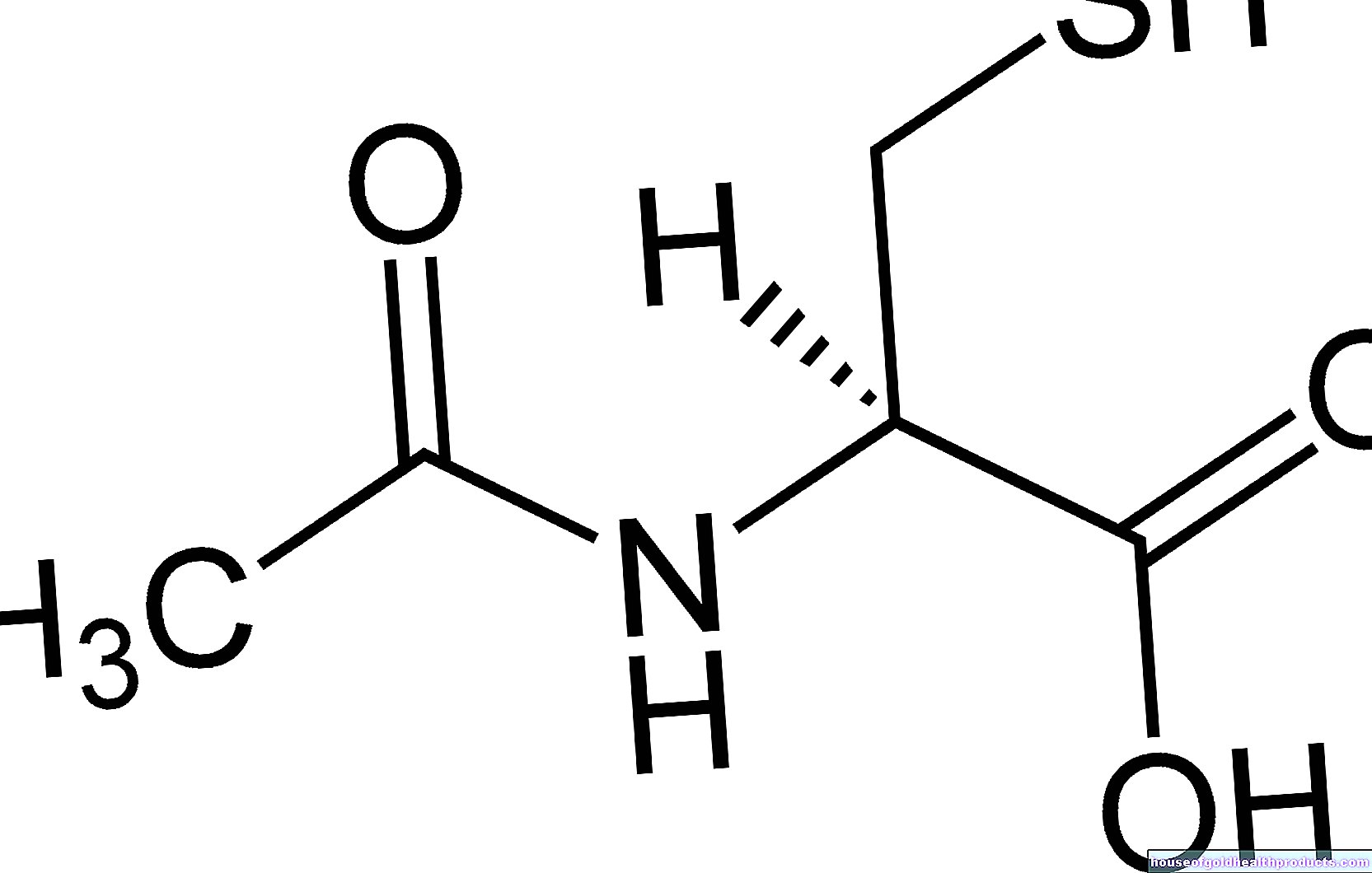

That's right. The patient came to us with severe cardiac insufficiency. At the same time he could barely see or hear and had inexplicable attacks of fever. It was really clear to me in five minutes that he had been poisoned by cobalt. But only because a few months earlier I had a Dr. House episode, which was also about metal poisoning.

How did the cobalt get into the patient's body?

Through a hip replacement operation. The patient originally had a ceramic femoral head, which, however, broke after a fall. This ceramic prosthesis was then replaced by a metal prosthesis. Obviously, the smallest ceramic splinters got into the joint space and abraded the metal.

What are the main difficulties you face in identifying diseases?

Logistic. We are overwhelmed with hundreds of inquiries and it is very difficult to filter out the cases where we can usefully help. And then it is unfortunately the case that our remuneration system is not at all made for solving complicated cases. For example, we recently had a patient with scurvy, a severe vitamin C deficiency. It was in the days of the seafarers, so you don't even think about the fact that it still exists today - and so it took a week to get a diagnosis. You earn many times more on a heart attack patient who is also in the clinic for a week.

Do you think this billing system helps prevent diseases from being recognized or treated incorrectly?

I wouldn't say it that hard. But I find that a fixed percentage, say three percent, of the allocation amounts of a university hospital for rare diseases should be reserved, which falls back to the payer if it is not used. Then every clinic would be desperately looking for patients with such diseases.

By the time people come to you, you have usually already completed a whole medical marathon. How great is the desperation of your patients?

Sometimes very large. You come here with a lot of confidence and hope. Unfortunately, we cannot always meet this requirement, we are just normal doctors, too.

A case in which you could help quickly and easily?

The other day we had a patient who went to the family doctor, the orthopedic surgeon, the radiologist and the neurosurgeon because of severe back pain. He said that after a few hours of sleep, he always woke up from back pain at night. I recommended that he buy a new mattress. After a few weeks he was no longer in pain - it was like a miracle healing.

Prof. Schäfer, thank you for talking to us.

Tags: toadstool poison plants smoking sleep