Trisomy 18

and Martina Feichter, medical editor and biologist Updated onFabian Dupont is a freelance writer in the medical department. The human medicine specialist is already doing scientific work in Belgium, Spain, Rwanda, the USA, Great Britain, South Africa, New Zealand and Switzerland, among others. The focus of his doctoral thesis was tropical neurology, but his special interest is international public health and the comprehensible communication of medical facts.

More about the expertsMartina Feichter studied biology with an elective subject pharmacy in Innsbruck and also immersed herself in the world of medicinal plants. From there it was not far to other medical topics that still captivate her to this day. She trained as a journalist at the Axel Springer Academy in Hamburg and has been working for since 2007 - first as an editor and since 2012 as a freelance writer.

More about the experts All content is checked by medical journalists.

Trisomy 18 (Edwards syndrome) is a genetic disorder in which chromosome 18 (or parts of it) are present in triplicate instead of double. This disrupts the development of a child in the womb and causes various organ malformations. Most of the young patients die before or soon after birth. Read more about the symptoms and consequences, causes, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of trisomy 18 here.

ICD codes for this disease: ICD codes are internationally recognized codes for medical diagnoses. They can be found, for example, in doctor's letters or on certificates of incapacity for work. Q91

Brief overview

- What is trisomy 18? A serious hereditary disease that is based on an incorrect distribution of chromosome 18 in the making of a child. The disease was first discovered in 1960 by the British Dr. John Edwards described. It is therefore also called Edwards syndrome.

- Frequency: In Europe, on average, one in 2,700 newborns is born with trisomy 18. Almost all of them are girls because affected boys usually die in the womb. The reason for this is not yet known.

- Possible symptoms: Depending on the degree of severity, for example, low birth weight, overlapping fingers, long and narrow skull, small mouth, receding chin, "faunal ears", "cradle feet", organ malformations (such as heart defects, cleft palate, malformations of the brain), failure to thrive and growth disorders , Breathing problems

- Causes: Chromosome 18 (or part of it) is present in all or some of the child's cells in triplicate - two copies would be normal. Most of the time, the mistake happens by chance during the baby's development. However, a higher age of the expectant mother is considered a risk factor.

- Treatment: Trisomy 18 is incurable. One can only try to alleviate the symptoms and consequences of the serious illness (e.g. tube feeding for problems with food intake or surgery for heart defects).

- Prognosis: Most children with trisomy 18 die in the womb or soon after birth. Patients who survive a little longer often show mental and physical disabilities and delayed development. With the rare mosaic trisomy 18, the prognosis can also be significantly better.

Trisomy 18: symptoms and consequences

Children born with trisomy 18 (Edwards syndrome) often show distinctive features. These include:

- low birth weight

- Finger overlays (the little finger overlaps the ring finger, and the index finger overlaps the middle finger)

- long, narrow skull

- small face skull, small mouth, small and receding chin

- Faun Ears (ears that taper upwards, but are set on low)

- "Cradle runners" (the shape of the sole is reminiscent of the runners of a cradle)

In addition, there are usually a large number of internal organ malformations. Some of the most common are:

- Cleft palate

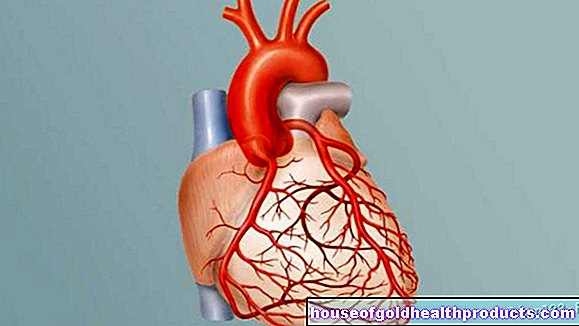

- Heart defect

- Kidney malformations

- Ureter malformations

- Malformation of the brain

- Pulmonary malformation

Affected children often have nutritional problems, failure to thrive, and breathing problems. Growth is delayed. Many of the little patients cannot walk freely and speak few words.

This full picture of trisomy 18 is particularly evident in children with the disease variant free trisomy. in which all body cells have a free trisomy. In contrast, especially in mosaic trisomy, the symptoms may be less pronounced, especially if only a few cell lines are affected by the chromosomal disorder.

Trisomy 18: causes and risk factors

A trisomy is a chromosome maldistribution in which chromosome 18 (or part of it) does not appear twice (as usual) but three times in a cell. The risk of this increases with the age of the expectant mother, for example.

Healthy cells in the body have 23 pairs of chromosomes (“double set of chromosomes”) - one of each pair comes from the mother and the other from the father. So there are 46 chromosomes in total. The germ cells (egg and sperm cells) only have a “simple set of chromosomes” (23 chromosomes), i.e. only one copy of each chromosome. When they were formed, the double set of chromosomes was halved. This is the only way to create a cell with a double set of chromosomes during fertilization through the fusion of an egg and a sperm cell. The new organism then emerges from this through countless cell divisions.

The mistake that leads to trisomy 18 sometimes happens during the formation of the germ cells. In other cases it only occurs after fertilization during the development of the fetus or embryo. According to this, doctors differentiate between different variants of trisomy 18:

Free trisomy 18

In free trisomy there is an incorrect distribution of chromosome 18 before the egg cell is fertilized. In more than 90 percent of cases, this incorrect assignment occurs during the formation of the egg cell (in the remaining cases during the formation of the sperm cell). This error often occurs spontaneously and rarely follows certain inheritance patterns.

Because the defect is already present in a germ cell (egg or sperm cell), it is also found in all body cells of the developing child: All cells have three (instead of two) copies of chromosome 18. The affected children show the full picture of the disease .

At around 94 percent, free trisomy 18 is the most common variant of the disease.

This is how free trisomy 18 arises

If the duplicate chromosomes 18 are wrongly not separated during egg cell formation, an egg cell contains three instead of two chromosomes 18 after fertilization - two from the egg cell and one from the sperm.

Mosaic trisomy 18

In mosaic trisomy 18, the error occurs relatively late in the development of the fertilized egg cell. Therefore, only individual cell lines have three chromosomes 18. All other cell lines have the normal number of two chromosomes 18 and are therefore healthy. The fewer cell lines that are affected, the lower the trisomy 18 symptoms and the higher the life expectancy of the affected child.

Mosaic trisomy 18 only accounts for about five percent of all cases of disease.

Translocation trisomy 18

The starting point for this variant is a so-called “balanced translocation” in one parent, usually the mother: She has the normal number of chromosomes in her cells. However, as a result of a chromosome break, part of chromosome 18 was incorrectly attached to another chromosome (translocation). However, since all genes of chromosome 18 are present in normal numbers (even if not in a normal arrangement), one speaks of “balanced translocation”. The affected parent is perfectly healthy.

When a child is conceived, however, the transmission of the translocation chromosomes can result in a child with an “unbalanced translocation” and thus a translocation trisomy 18: A part of chromosome 18 is present in triplicate. Doctors also speak of a partial trisomy as a result of a translocation.

About one percent of all trisomy 18 patients have a translocation trisomy.

Second most common trisomy

In addition to trisomy 18, there are other trisomies - chromosomal disorders with an extra chromosome (or extra chromosome parts). The most common is trisomy 21 (Down syndrome). Trisomy 18 and trisomy 13 (Patau syndrome) follow in second and third place. Children who have any of these three trisomies are potentially viable. In contrast, unborn children with other trisomies die very early in development. In these cases, pregnancy is often not even noticed.

Trisomy 18: examinations and diagnosis

If a gynecologist detects abnormalities in the unborn child during the regular ultrasound examinations during pregnancy, he can suspect a chromosomal disorder such as trisomy 18. These suspicious abnormalities include, for example, delayed growth and abnormalities in the child's abdomen, head or heart that fit into the picture of trisomy 18. In addition, with trisomy 18 it often happens that only one artery (instead of two) is created in the umbilical cord. The amount of amniotic fluid can also be an indication of an illness.

Triple test

In addition, certain maternal blood values can be increased in a trisomy. This blood test is also known as the triple test or MoM test (multiples of the median). It helps identify unborn babies who are at increased risk of trisomy. However, the triple test does not allow a reliable diagnosis! He can only estimate the risk of certain chromosomal disorders in the child. If the measured values are conspicuous and the parents-to-be want to be certain, invasive examinations are necessary.

Despite its low informative value, the triple test has one major advantage: In contrast to more precise invasive examinations (such as amniotic fluid examinations), it does not pose any risks to pregnancy or the unborn child.

Invasive examinations

In order to clarify a suspicion of trisomy 18, the doctor can carry out an invasive examination method: He can take a tissue sample of the placenta (chorionic villus sampling) or some amniotic fluid (amniocentesis). Child cells are found in both samples. Their genome is examined in the laboratory for chromosomal disorders such as trisomy 18.

In both invasive examinations, taking a sample can harm the child and possibly even cause a miscarriage.

Chromosome analysis using a blood sample

Traces of the child's genetic makeup (DNA) can also be found in the blood of a pregnant woman. For some time now it has been possible to isolate this child's DNA from the mother's blood and examine it for chromosomal disorders in the laboratory. These prenatal blood tests include, for example, the Harmony test, PrenaTest and Panorama test.

In contrast to invasive methods of prenatal diagnosis (such as amniocentesis), these blood tests are not dangerous for the unborn child. However, you can also detect an existing trisomy (such as Edwards syndrome) with a high degree of reliability.

The DNA test can usually be offered from the 10th week of pregnancy. If there is a justified suspicion of trisomies and after a medical consultation, the costs for such a test can be covered by the statutory health insurance.

Sufficiently justified suspicions exist, for example, in high-risk pregnancies: women are considered to be high-risk pregnancies if an ultrasound examination or first-trimester screening revealed abnormalities in the unborn child. The attending physician can also suggest a prenatal blood test for older pregnant women or those with a family history.

Trisomy 18: treatment

Trisomy 18 cannot be cured. All therapeutic measures aim only to alleviate the child's symptoms or to maintain the organ functions. For example, if the child has nutritional problems, special teats or tube feeding can be helpful. In the event of breathing problems, breathing can be monitored on a monitor.

The very common heart defects are sometimes operated on. Surgery can also be performed for other organ malformations such as urinary flow disorders. In general, however, surgical corrections of malformations are carefully considered because it is unclear whether they actually improve the prognosis and quality of life of the young patients.

In many cases it makes sense to give the parents psychological advice, as the death of the child can usually be expected. The life of the newborn is particularly at risk in the first few weeks of life.

Trisomy 18: disease course and prognosis

More than 95 percent of all children with trisomy 18 still die in the womb, often in the first trimester of pregnancy. The life expectancy of live born trisomy 18 children is not very high. If the organ malformations are known before the birth, the delivery can take place on a maternity ward with subsequent pediatric maximum care. This can increase the child's chances of survival.

The average life expectancy of trisomy 18 children is one to two weeks. Only five percent reach the first year of life, and only one percent experience the age of ten. In individual cases, however, the prognosis depends on various factors. Above all, this includes the type of trisomy 18: Small, partial trisomies and light mosaic trisomies have a better prognosis than a free trisomy 18.

Even if the child survives its first birthday, one must reckon with severe physical and mental disabilities and developmental delays. In addition to organ malformations, many children are prone to seizures, severe postural deformity and problems with eating. In rare cases, patients with trisomy 18 reach adolescence. There have also been reports of individual trisomy 18 patients who survived through age 27.

The unfavorable prognosis applies particularly to the full picture of the disease - free trisomy 18. It is by far the most common variant of the disease. The rarer mosaic trisomy 18 often has a better prognosis. In some cases, the development of the child can be almost normal if only a few cell lines are affected by the chromosomal disorder.

The psychological burden on parents, who live with the certainty that their child may suddenly die, should not be underestimated. Parents of trisomy 18 children should therefore take advantage of the various advice and support services.

Additional information

Support group:

- LEONA e.V. - Association for parents of chromosomally damaged children

Tags: book tip healthy feet dental care

.jpg)

.jpg)