Ventricular septal defect

Astrid Leitner studied veterinary medicine in Vienna. After ten years in veterinary practice and the birth of her daughter, she switched - more by chance - to medical journalism. It quickly became clear that her interest in medical topics and her love of writing were the perfect combination for her. Astrid Leitner lives with daughter, dog and cat in Vienna and Upper Austria.

More about the experts All content is checked by medical journalists.Doctors refer to one or more "holes" in the septum between the right and left ventricle as a ventricular septal defect (VSD). The VSD is the most common congenital heart defect. Read here how the disease develops, which symptoms occur and when a ventricular septal defect has to be operated on!

ICD codes for this disease: ICD codes are internationally recognized codes for medical diagnoses. They can be found, for example, in doctor's letters or on certificates of incapacity for work. Q21

Brief overview

- What is a VSD? Congenital heart defect in which there is at least one hole between the right and left ventricles

- Treatment: Closure of the hole with open heart surgery or with a cardiac catheter. Medicines are only used temporarily and are not suitable as long-term therapy.

- Symptoms: Small holes rarely cause discomfort, larger defects lead to breathing problems, poor drinking, little weight gain, heart failure, pulmonary hypertension.

- Causes: Malformation in the embryonic development, very rarely acquired through an injury or a heart attack

- Risk factors: genetic changes, diabetes during pregnancy

- Diagnosis: Typical symptoms, cardiac ultrasound, if necessary ECG, X-ray, CT, MRT

- Prevention: VSD is usually congenital, so there are no measures to prevent the hole in the heart.

What is a ventricular septal defect?

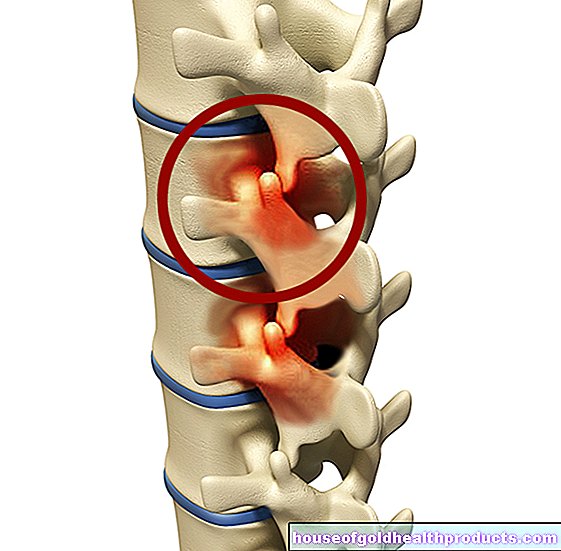

Doctors call a ventricular septal defect (VSD) a "hole" in the septum (septum) between the right and left ventricles. There is a connection between the otherwise separate heart chambers. In almost all cases, the heart defect is congenital; only in rare cases does the VSD develop in the course of life, for example through an injury or a heart attack.

Classification of ventricular septal defects

If there is only a single hole, doctors speak of a "singular VSD"; somewhat less often there are several defects in the heart septum. Doctors refer to these as "multiple ventricular septal defects".

An “isolated VSD” is when the hole is the only malformation in the newborn. In other cases, the hole in the heart occurs in conjunction with other diseases. These include cardiac malformations such as the Fallot tetralogy (malformation of the heart), the transposition of the large arteries (main and pulmonary arteries are reversed) or a univentricular heart (the heart consists of only one ventricle).

It is not uncommon for VSD to occur in connection with syndromes such as trisomy 13, trisomy 18 or trisomy 21 (also known colloquially as Down's syndrome).

Doctors also classify septal defects according to where they occur: the upper part of the septum consists mainly of connective tissue (membrane), and the lower part of muscles, the transitions are fluid.

- Membranous VSD: Holes in the connective tissue part of the septum are rare (5 percent of all VSD), but tend to be large.

- Perimembranous VSD: In a perimembranous VSD, the defect is at the transition between connective tissue and muscles. 75 percent of all VSD are in the muscular part, but mostly extend to the membranous part and are therefore referred to as "perimembranous".

- Muscular VSD: Purely muscular VSD are rare at 10 percent, and there are often several small defects.

frequency

At 40 percent, the ventricular septal defect is the most common congenital heart defect. It occurs in about five in 1,000 newborns, with girls being slightly more likely to be affected. The ratio between affected boys and girls is around 1: 1.3.

Normal blood circulation

The heart consists of two atria (right and left atrium) and two chambers (right and left ventricle). A wall separates the two atria and the chambers from each other. There is a large heart valve between the atrium and ventricle on both sides.

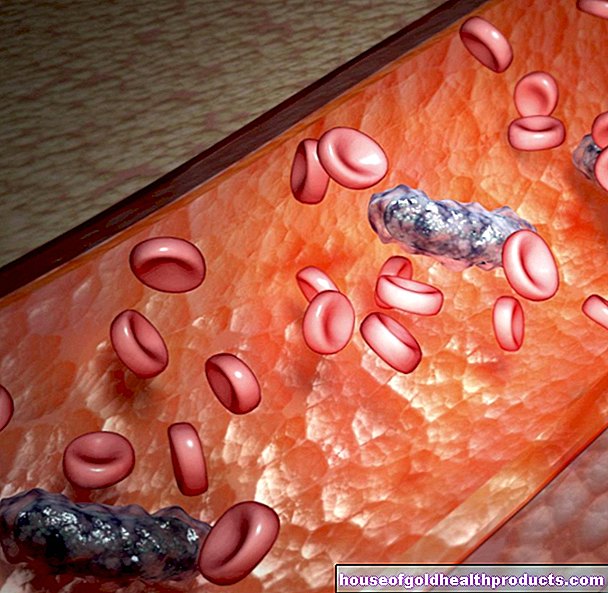

The oxygen-poor blood reaches the right atrium via the upper and lower vena cava and is pumped from there via the right ventricle into the pulmonary arteries. In the lungs, the blood is enriched with oxygen and flows back to the left atrium via the pulmonary veins. The left ventricle pumps the oxygen-rich blood into the body's circulation via the main artery (aorta).

Change in ventricular septal defect

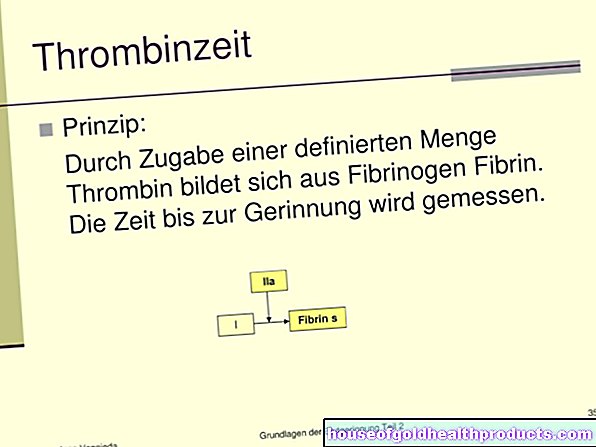

In the case of a ventricular septal defect, there is a small hole, sometimes several small holes, in the wall (septum) between the right and left ventricle. Because the pressure in the left ventricle is usually higher than that in the right, some of the oxygen-rich blood flows from the left ventricle through the hole back into the right one. Doctors speak of a "left-right shunt". The result: More blood than usual flows into the pulmonary circulation, the blood pressure in the pulmonary vessels rises (pulmonary high pressure), which permanently damages them. In addition, both heart chambers are overloaded by the increased blood flow, which in the long term leads to cardiac insufficiency.

When does a VSD have to be operated?

Whether and how a ventricular septal defect is treated depends on how big the hole is, what shape it is, and where exactly it is.

A small hole usually does not cause discomfort and does not require treatment. In addition, it is possible that the hole will shrink over time or close by itself. This is the case in about half of the patients: In them, the VSD closes within the first year of life.

Medium, large, and very large holes are always operated on. Depending on the individual case, there are different surgical methods to close the hole.

Open heart surgery

Open heart surgery is performed using a "heart-lung machine". This is a medical device that temporarily takes over the functions of the heart and lungs: the oxygen-poor blood enters the device via a needle (cannula) in the right atrium of the heart, where it is enriched with oxygen and passed through the main artery fed back. The blood circulation is shut down for a short time so that it is possible to operate on the open heart.

The doctor first opens the chest and then the right atrium. The defect on the septum of the heart is visible through the atrial valve (tricuspid valve). The doctor then closes the hole with the body's own tissue from the pericardium or with a plastic plate (patch). The heart covers the material with its own tissue in a short time. No rejection reactions are to be feared with this method. The operation is now one of the routine operations and involves only minor risks. Patients in whom the hole in the heart has been closed are then considered to be cured.

Cardiac catheter

Another possibility to close the ventricular septal defect is the so-called "interventional closure". The heart is not accessed via an operation, but via a catheter that is advanced into the heart via the inguinal vein. The doctor positions a "umbrella" in the area of the defect over the catheter and thus closes the hole.

Medication

Therapy of a ventricular septal defect with medication is not possible. In some cases, however, VSD patients are given medication to stabilize them until surgery. This is the case, for example, when infants or children are already showing symptoms or are too weak for an immediate operation.

The following drugs are used:

- Antihypertensive agents such as beta blockers, water medicines (diuretics) and so-called aldosterone receptor antagonists for signs of heart failure.

- If the weight gain is too low, those affected are given a special diet high in calories.

Some patients receive medication for a few weeks after the hole has been closed by surgery to relieve the heart and lungs.

Symptoms

The symptoms of a VSD depend on the size of the hole in the septum of the heart.

Symptoms of small VSD

Small defects in the septum usually do not cause any discomfort. In about half of the cases, the hole becomes even smaller over time and closes on its own. Babies born with a small septal defect are usually normal and have no symptoms. Treatment is not necessary.

Symptoms of medium and large VSD

Medium and large holes in the septum damage both the heart and pulmonary arteries over time. As the heart has to pump more blood through the heart, it becomes increasingly congested. The result: the heart chambers enlarge and cardiac insufficiency develops.

Typical symptoms are:

- Shortness of breath, rapid breathing, and shortness of breath

- Drinking weakness: Babies are too weak to drink enough.

- Lack of weight gain, failure to thrive

- Increased sweating

- Lower respiratory tract more susceptible to infection

Because of their weakness, it is not always possible to operate on affected babies immediately. Until then, temporary medication may be necessary.

Symptoms of very large ventricular septal defects

If the holes in the septum are very large, a corresponding amount of blood flows from one heart chamber to the other. As a result, the pressure conditions in the heart chambers and in the pulmonary vessels equalize. The vessel walls are not adjusted to such a pressure load and “harden” due to the permanently high pressure (pulmonary hypertension). These changes cannot be reversed.

Finally, it is possible that the direction of blood flow is reversed: low-oxygen blood enters the bloodstream and the organism is no longer adequately supplied with oxygen. This lack of oxygen is visible as a blue discoloration of the skin (cyanosis). Doctors speak of the so-called "Eisenmenger reaction" in connection with a VSD. Patients who have already developed this condition have a significantly reduced life expectancy.

It is particularly important to operate on patients with very large defects in infancy or childhood, before changes in the pulmonary vessels occur!

Causes and Risk Factors

Causes of a "Hole in the Heart"

Primary VSD: Ventricular septal defects are almost always congenital. Doctors speak of a "primary VSD". The causes of primary VSD are either insufficient growth of the septum during embryonic development or errors in the connection between its individual sections during the fourth to eighth week of pregnancy.

Secondary VSD: In a secondary ventricular septal defect, newborns are born with a completely closed septum. The hole in the septum arises afterwards, for example due to an injury, an accident or a heart disease (heart attack). Secondary (acquired) VSD are extremely rare.

Risk factors for a "hole in the heart"

Changes in the genetic make-up: Sometimes ventricular septal defects occur in combination with other genetic diseases. These include, for example, certain chromosome defects such as trisomy 13, trisomy 18 and trisomy 21. VSD is also known to have a family history: it occurs more frequently when parents or siblings have a congenital heart defect. The risk is three times higher if a sibling has a VSD.

Maternal Disease During Pregnancy: Children of mothers who develop diabetes mellitus during pregnancy are at increased risk of VSD.

Investigation and diagnosis

Before birth

Larger defects in the septum may be detectable before birth.

If the child is in a favorable position, this is possible with targeted examinations (such as the "malformation sound" between the 19th and the 22nd week of pregnancy). If such a defect is found, further examinations will follow to see how the defect develops.

Important to know: It is possible that the hole in the heart closes again in the womb. According to the latest findings, this is the case with up to 15 percent of all affected children.

After birth

Neonatal examination

Every newborn is examined for various diseases after birth. This includes listening to the heart. Ventricular septal defects usually cause a typical heart murmur. In babies (up to the fourth week of life), however, it is possible that the typical heart murmur is imperceptible to the doctor. The reason for this is that it takes up to four weeks for the pulmonary circulation to finally change after the birth. If a characteristic heart murmur can be detected after the fourth week of life or if the newborn is already showing symptoms of a VSD, the pediatrician will refer the baby to a cardiologist.

Cardiac ultrasound

If a VSD is suspected, the cardiologist will perform an ultrasound scan of the heart. This is usually a good way of proving a hole in the heart. The doctor will assess the location, size, and structure of the defect. The examination takes a short time and is painless for the baby.

Further investigations

In some cases, the doctor will do more tests to get more detailed information about the defect in the septum. These include the electrocardiogram (EKG) and X-ray examinations, and less often computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Course of the disease and prognosis

Smaller VSDs often go unnoticed and usually do not require treatment because they have no effect on resilience or life expectancy. In addition, in about half of those affected, they close by themselves within the first year of life. After the first year of life, however, the probability of a spontaneous closure decreases significantly.

Even patients with larger defects have a normal life expectancy if they are treated in time and the hole has been successfully closed. Both the heart and the lungs are then able to take normal loads.

In the case of very large defects, the prognosis depends on whether the hole in the heart is discovered and treated early. If left untreated, cardiac insufficiency and high pressure in the pulmonary arteries (pulmonary hypertension) develop.These diseases usually shorten life expectancy: Without treatment, those affected often die in young adulthood. But if they are treated before the corresponding diseases develop, they have a normal life expectancy.

Aftercare

All patients diagnosed with VSD should have regular check-ups. In some cases, problems do not arise until adulthood: If there is cardiac arrhythmia or inflammation of the inner lining of the heart (endocarditis), treatment is necessary. H2: prevent

In most cases, a ventricular septal defect is congenital. There are therefore no measures to prevent the hole in the heart.

Prevent

In most cases, a ventricular septal defect is congenital. There are therefore no measures to prevent the hole in the heart.

Tags: Baby Child pregnancy birth teenager

.jpg)

-bei-kindern.jpg)