Prostate cancer: treatment

and Tanja Unterberger, medical editor Updated onAstrid Leitner studied veterinary medicine in Vienna. After ten years in veterinary practice and the birth of her daughter, she switched - more by chance - to medical journalism. It quickly became clear that her interest in medical topics and her love of writing were the perfect combination for her. Astrid Leitner lives with daughter, dog and cat in Vienna and Upper Austria.

More about the expertsTanja Unterberger studied journalism and communication science in Vienna. In 2015 she started her work as a medical editor at in Austria. In addition to writing specialist texts, magazine articles and news, the journalist also has experience in podcasting and video production.

More about the experts All content is checked by medical journalists.

How prostate cancer is treated depends on how far the disease has progressed. An early-stage tumor that has not yet grown into the surrounding tissue can usually be completely healed. For advanced prostate cancer, modern drugs or radiation can help prevent the disease from progressing. If the cancer has already metastasized, a cure is no longer possible. Read here what treatment options are available - from controlled waiting to surgery and radiation therapy to hormone therapy!

ICD codes for this disease: ICD codes are internationally recognized codes for medical diagnoses. They can be found, for example, in doctor's letters or on certificates of incapacity for work. C61

How is prostate cancer treated? Individual choice of therapy

Various forms of therapy are available for the treatment of prostate cancer. How the tumor is treated in each individual case essentially depends on the age of the patient and on how far the cancer has already progressed and how aggressively it is growing. The patient's personal attitude towards treatment also plays a role in the therapy decision. Ideally, the patient makes the decision about prostate cancer treatment together with the attending physician, taking into account all factors.

The following factors influence the therapy decision:

Age: Most malignant prostate tumors grow very slowly, sometimes not at all. The older the patient, the less likely it is that the disease will lead to death: for most older men with prostate cancer, it is not the cause of death. For curative (healing-oriented) treatment such as surgery, radiation therapy or active monitoring, the statistical life expectancy of the man should be at least ten years. This is generally the case for men who are around 70 years old and in good health according to their age.

General condition: Other existing diseases such as cardiovascular diseases may significantly reduce life expectancy. In addition, diseases such as heart failure make certain forms of treatment for prostate cancer such as surgery impossible.

PSA value: A very high or rapidly increasing PSA value is an argument in favor of a rapid start of therapy because it suggests a high level of tumor activity

The extent and aggressiveness of the tumor: The decisive factor in therapy planning is how far the prostate cancer has progressed and how aggressively it grows.

The attending physician will explain to you in detail which form of prostate cancer treatment he thinks is most suitable in your case. This conversation should take place calmly and without time pressure. You can also take your partner, family member or friend with you for a conversation: Many patients find themselves in a state of emergency after being diagnosed with cancer and can barely absorb the amount of new information in this situation. Experience has shown that “four ears” pick up more of such a conversation. You can also take notes during the conversation. Don't be afraid to ask if you don't understand something. Don't let yourself be rushed into therapy.

Diagnosing prostate cancer is not an emergency! Take enough time to inform yourself and, together with the doctor, to make a therapy decision that is right for you!

The following is an overview of the different prostate cancer treatment options: You will learn how the different procedures work, when they are used, and what their advantages and disadvantages are.

What are the treatment options for prostate cancer?

The ways to treat prostate cancer have evolved significantly over the past few decades. There are now several treatments available that completely heal the tumor or curb tumor growth. If the cancer is already well advanced and has metastasized, treatment aims to extend the life span and alleviate symptoms.

Not all therapies are suitable for every patient, but there are one or more alternative treatment options for each patient.

The following treatment options are currently available:

- Controlled waiting ("watchful waiting")

- Active surveillance

- Operation: Removal of the prostate ("radical prostatectomy = total prostatectomy")

- Radiation therapy (prostate cancer radiation from outside or inside)

- Hormone therapy

- chemotherapy

- Other therapies such as cold therapy and HIFU therapy ("high intensity focused ultrasound")

How good are the chances of a cure for prostate cancer?

Prostate cancer grows very slowly compared to other cancers. If the tumor is limited to the prostate, it can usually be completely cured.

The chances of a cure in advanced prostate cancer are not as good as in the early stages. But thanks to modern treatment options, the mean survival time has increased significantly. In some cases, the tumor can even be cured with surgery or radiation.

If the cancer has already metastasized, the disease can no longer be cured. With hormone withdrawal treatment (with or without chemotherapy or radiation therapy), however, the progression of the disease can be slowed down, so that many men live with their tumor disease for a long time. Metastases can be treated in a targeted manner.

Prostate cancer treatment: surgery

If the tumor is still completely confined to the prostate and has not spread beyond the prostate capsule, surgery can usually completely cure it. To do this, the prostate and the capsule surrounding it, the part of the urethra that runs through the prostate, the seminal vesicles, the vas deferens and part of the bladder neck must be removed. Doctors call this procedure a radical prostatectomy or total prostatectomy.

Access to the prostate is possible in three different ways:

- Incision in the lower abdomen between the pubic bone and the navel (retropubic radical prostatectomy)

- Laparoscopy (minimally invasive laparoscopic prostatectomy, "keyhole technique")

- Perineal incision (perineal radical prostatectomy)

If it is suspected that neighboring lymph nodes are also infected with cancer cells, these are also removed (lymphadenectomy) and then examined under the microscope (histopathologically). If cancer cells are found in it, further treatment is needed.

Radical prostatectomy should not be confused with TURP (transurethral resection of the prostate). The prostate is “peeled out” of its capsule through the urethra, while the prostate capsule remains in the body. TURP is only used to treat benign enlargement of the prostate (benign prostatic hyperplasia, BPH).

Surgery risks

Thanks to new surgical techniques, side effects and complications of prostate cancer surgery are much rarer today than in the past. Still, it's important to know about the risks of the procedure. Under certain circumstances, after the operation, you may experience dripping (urinary incontinence) and impotence ("erectile dysfunction").

Dripping urine (incontinence)

After prostate cancer surgery, the sphincter that opens and closes the urinary bladder is weakened. Affected people can no longer hold the urine. This means that larger or smaller amounts of urine leak out in an uncontrolled manner. Doctors refer to the leakage of urine as incontinence.

Not being able to hold the urine severely limits the quality of life: Many of those affected are ashamed and withdraw from social life. However, there are ways to train the weakened sphincter: Through targeted pelvic floor training, around 95 percent of men can hold their urine again after prostate cancer surgery. If this does not succeed, the doctor reinforces the sphincter muscle ("artificial sphincter") in another operation. In addition, insoles help to catch the urine that flows out.

Impotence (erectile dysfunction)

The prostate cancer surgery can injure two nerve cords that are necessary for a normal erection of the penis. The nerve cords run directly along the prostate on both sides. You can only be spared during prostate cancer surgery if the tumor is still small and has not yet spread to the surrounding tissue. Before the operation, the surgeon can roughly estimate whether such a "nerve-conserving operation" will be possible - but he cannot promise it. The full extent of the tumor spread can only be seen during the operation. For optimal chances of recovery, the entire tumor tissue must be removed - if necessary, with damage to the aforementioned nerves. If the patient actually suffers from erectile dysfunction as a result, various medications and aids can help to achieve a largely normal erectile function.

Prostate Cancer Treatment: Hormone Therapy

In most patients, prostate cancer grows in a hormone-dependent manner: This means that the male sex hormone testosterone promotes the growth of the tumor. Hormone therapy for prostate cancer aims to stop this growth. It lowers testosterone levels and slows down the growth of cancer cells for some time.

Hormone therapy is used when the prostate cancer has already metastasized in lymph nodes, bones or other organs. A cure is not possible with hormone therapy alone, but it makes sense in combination with other therapies such as radiation therapy for advanced prostate cancer. The aim of treatment is to delay the progression of the disease and relieve symptoms.

The hormone therapy does not have a permanent effect, the cancer cells grow after about 1.5 to two years even without the influence of testosterone. Doctors then speak of a "castration-resistant prostate cancer".

There are different forms of hormone therapy. Their common goal is to slow down tumor growth. This is achieved in different ways: some hormone treatments block the production of testosterone in the testes, others prevent the hormone from acting on the tumor cells.

Operative hormone withdrawal (surgical castration)

Most testosterone is produced in the testes, with a small amount in the adrenal glands. If the testicles are surgically removed, the testosterone level drops permanently. This form of hormone therapy cannot be reversed and is therefore a psychological burden for many patients. For this reason - and because there are now effective drugs to lower testosterone levels - castration is rarely carried out.

Chemical hormone withdrawal (hormone withdrawal therapy, chemical castration)

In this form of treatment, medication is used to lower testosterone levels. It is used when the tumor is already advanced and has metastasized or an operation is not possible. It is usually combined with radiation or chemotherapy.

The following hormones can be used to treat prostate cancer:

GnRH analogues: GnRH is a hormone that stimulates the pituitary gland to release the hormones LH (luteinizing hormone) and FSH (follicle-stimulating hormone). LH causes testosterone to be produced in men, FSH allows the sperm to mature in the testicles.

GnRH analogues act like natural GnRH. If the patient receives GnRH, the pituitary gland releases LH and FSH, and the testosterone level initially increases. With long-term use, however, the pituitary becomes insensitive to GnRH, it releases less LH, which means that the testes produce less and less testosterone. After a few weeks, the testosterone level drops significantly. GnRH analogues are administered monthly or every three (or six) months as a depot injection.

GnRH antagonists: GnRH antagonists are opponents of the natural GnRH. They do not suppress the formation, but the effects of testosterone. GnRH antagonists block the docking sites (receptors) for GnRH in the pituitary gland and thereby prevent the release of LH, the testosterone level drops within a short time. However, they are currently only available as a 1-month dose, so that patients need a depot injection every month.

"Androgens" is the medical term for male sex hormones, the main representative of which is testosterone. Antiandrogens cancel out the effect of these sex hormones. They block the docking points for testosterone in the tumor cells of the prostate and thus prevent its growth-promoting effect. Antiandrogens are administered as tablets and are divided into steroidal and nonsteroidal antiandrogens according to their chemical structure.

In the course of hormone treatment, the tumor cells develop various mechanisms to circumvent the testosterone deficiency. A very small amount of testosterone is then sufficient for the tumor to continue to grow. Doctors speak of a "castration-resistant prostate cancer".

The active ingredient abiraterone not only inhibits testosterone production in the testes, but also in the adrenal glands (where small amounts of testosterone are produced) and in the tumor tissue itself. This suppresses all testosterone production. This form of treatment is only used for metastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer. Abiraterone is taken daily as a tablet.

In principle, it is also possible to inhibit the effect of testosterone with female sex hormones (estrogens). Due to the possible side effects (such as thrombosis), this therapy is rarely used.

Hormone therapy: side effects

In addition to the desired effect of hormone withdrawal, hormone therapy is also associated with side effects. The symptoms are roughly comparable to those that occur in women during the menopause.

Possible side effects are:

- Hot flashes

- Chest pain or enlargement (gynecomastia)

- Weight gain

- Muscle breakdown

- Bone loss (osteoporosis)

- Anemia

- Decreased sexual desire (loss of libido)

- Decrease or loss of erectile function (erectile dysfunction)

- Infertility (infertility)

Talk to your doctor about side effects! Some of these undesirable effects, such as hot flashes and breast enlargement, can be treated well!

Prostate Cancer Treatment: Radiation Therapy

In radiation therapy (radiotherapy), the tumor is “bombarded” with ionizing rays (X-rays). The aim of treatment is to damage the cancer cells so that they lose their ability to divide and die.

Radiation is sometimes used in prostate cancer treatment when surgery is not possible (poor general condition) or is refused by the person concerned. However, it can also be performed in addition to an operation to remove tumor cells that could not be removed by the procedure.

Irradiation from outside or inside

Irradiation of the prostate is possible from the outside and inside.

If the tumor is irradiated from the outside through the skin, doctors speak of percutaneous or external radiation therapy. The X-rays are aimed precisely at the tumor with a so-called linear accelerator in order to protect healthy tissue as much as possible. The irradiation takes place several times a week for seven to nine weeks, with a single irradiation session only lasting a few seconds to minutes.

In the case of radiation from the inside (brachytherapy), the principle is different: Here the doctor brings the radiation source (radioactive substances) directly into the tumor. Brachytherapy is an option if the tumor is still locally limited and has not metastasized. There are two options for this form of treatment:

In "Low-Dose-Rate-Brachytherapy" (LDR), small, hollow needles are used to insert small, radioactive metal particles - so-called "seeds" - into the prostate via the perineum. They emit their radiation over a very short distance, but only radiate for a few weeks. Because of this, they can stay in the prostate permanently and do not need to be removed. The “seeds” are implanted under general or local anesthesia.

In "high-dose-rate brachytherapy" (HDR), metal particles are also introduced into the prostate. This is done using hollow needles that only remain in the prostate tissue for the duration of the treatment. In contrast to the "seeds", the metal bodies in HDR emit a higher dose of radiation over a very short distance and are removed again after a few minutes of irradiation via the hollow needles.

The treatment is usually carried out twice with an interval of a few days and is also carried out under local or general anesthesia. Patients usually remain in the hospital for the time between the two treatments. In addition to HDR, they usually receive external radiation therapy for several weeks.

The "High Dose Rate Brachytherapy" (HDR) is also called brachytherapy with afterloading procedure.

Irradiation: side effects

With the help of radiation therapy, it is possible to kill cancer cells in a targeted manner. However, it cannot be ruled out that healthy neighboring tissue may also be affected.

Acute side effects occur immediately after radiation therapy. These include irritation and reddening of the skin, but also inflammation of the mucous membrane of the bladder and urethra. This is noticeable, for example, by a burning sensation when urinating. Irritation and inflammation of the mucous membrane in the rectum is also possible. Then pain during bowel movements, easy bleeding and diarrhea can occur.

The acute side effects usually subside after the end of the radiation therapy. The doctor may prescribe medication for relief.

In some patients, prostate cancer radiation therapy causes chronic side effects or long-term effects. These can be, for example, an increased tendency to diarrhea and persistent bowel changes. Permanent changes in the bladder and urethra as well as urinary incontinence are possible. Some patients also develop erectile dysfunction as a result of radiation. Last but not least, any radiation therapy can lead to a second tumor developing years or decades later in the irradiated area. For ex-prostate cancer patients, this can be rectal cancer, for example.

The likelihood and extent of side effects depend on the type and intensity of radiation therapy.

Controlled waiting ("watchful waiting")

Sometimes prostate cancer grows very slowly or not at all and does not cause any symptoms for a long time. In older men, it is therefore possible that the tumor disease does not cause any health problems. The likelihood that the cancer will be dangerous for them is small. In contrast to "active monitoring", there are no control examinations when waiting in a controlled manner. The doctor only initiates treatment if symptoms arise. This can be pain caused by metastases in the bones, for example.

"Watchful waiting" is useful, for example, for very old patients or for those whose life expectancy is less than ten years. Even with patients who also have other illnesses such as high blood pressure or heart disease, one often opts for "watchful waiting" for a small, less aggressive prostate carcinoma. This saves them the burden and possible side effects of a healing-oriented prostate cancer therapy.

Active surveillance

The principle of active monitoring is similar to that of controlled waiting: There is no treatment initially, but the doctor checks how the tumor is behaving at short intervals. If it is growing very slowly, it may not need treatment at all. Active monitoring saves many men from treatment that is fraught with side effects. However, it is only an option if the patient meets certain requirements. This includes, for example, that the prostate cancer is very small and limited to the prostate and does not grow aggressively.

In the first two years after the diagnosis, the doctor checks every three months (every six months if the PSA value remains the same) to see whether the tumor has changed. To do this, he scans the prostate (digital rectal examination) and determines the PSA value (blood sample). In addition, the prostate is examined using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). This means that even the smallest changes in the prostate can be made visible. If the MRI shows an abnormal finding, the doctor takes a tissue sample (biopsy) and examines it under the microscope.

This close monitoring enables the doctor to discover early on when the prostate cancer is progressing and initiate appropriate treatment.

Discuss with your doctor whether active monitoring is an option for you.

Prostate Cancer Treatment: Chemotherapy

Similar to hormone therapy, chemotherapy also works throughout the body; doctors speak of “systematic therapy”. The doctor gives certain drugs (so-called cytostatics) via the vein, which prevent the growth and division of tumor cells. Chemotherapy not only reaches tumor cells, but also other fast-growing cells such as hair follicles, which leads to hair loss in many patients.

Chemotherapy for prostate cancer can be considered if the tumor has already metastasized. It is often combined with hormone therapy.

Chemotherapy: side effects

Cytostatics act not only on tumor cells, but also on healthy cells that normally divide rapidly. This also includes hair follicles, which is why chemotherapy patients often lose their hair. Other side effects of the cytostatics can include skin problems, nail changes, nausea and vomiting, and changes in the blood count (lack of white and red blood cells).

Other therapy methods

If the prostate cancer has not yet spread beyond the connective tissue prostate capsule, there is always the option of cold therapy (cryotherapy). The tumor tissue is frozen in the process. According to current expert opinion, cold therapy is not suitable for the treatment of localized prostate cancer. It is currently only carried out in the context of studies.

Another option for prostate cancer treatment for a locally limited tumor is a special ultrasound therapy, the so-called HIFU (high-intensity focused ultrasound). The tissue is strongly heated with ultrasound waves and destroyed in this way. The ultrasound is aimed either at the entire prostate (whole gland therapy) or only at the limited tumor (focal therapy). The HIFU is still considered an experimental procedure for which there is hardly any long-term experience. For the time being, this form of therapy is only being used in the context of studies.

Some other methods of prostate cancer treatment have so far only been recommended within studies, for example irreversible electroporation (IRE) and vascular photodynamic therapy (VTP).

Treatment of metastases

In the advanced stage, a malignant prostate tumor has often already formed settlements in other parts of the body (metastases). Most often these are bone metastases. In some patients they do not cause any symptoms. Often, however, they cause pain and make the affected bones more fragile. If there are metastases in the bones, these are irradiated. This can stop the bone from deteriorating, prevent broken bones, and relieve pain.

In addition, it is possible for the doctor to prescribe medication. These can be pain relievers or bisphosphonates - active ingredients against bone loss.

In certain cases, what is known as radionuclide therapy can also be used for bone metastases. This is a kind of irradiation from the inside: the patient receives radiating chemicals by infusion, which the body builds specifically into the bone metastases. The radiation emitted over a short distance destroys the cancer cells.

If possible, attempts are made to surgically remove bone metastases. Patients then usually also receive radiation therapy.

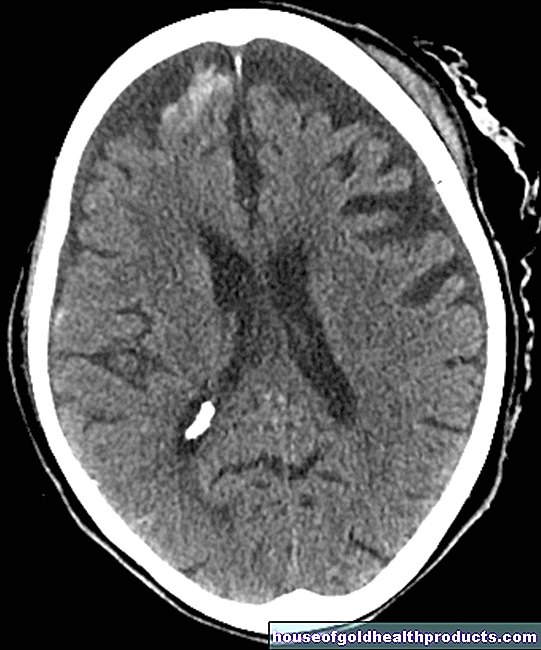

In addition to bone metastases, advanced prostate cancer may also form metastases in the liver, lungs, or brain. If possible, prostate cancer treatment also includes measures that target the daughter tumors (radiation therapy, chemotherapy, possibly surgery, etc.).

Aftercare

When prostate cancer treatment is complete, follow-up care begins. It aims to improve the quality of life of patients and to detect relapses in good time. This is important because around three out of ten men will develop new tumors over the next few years. This can either be at the original location (“local recurrence”) or in another region of the body (metastases).

Follow-up care usually begins twelve weeks after the end of therapy. It is usually sufficient to determine the PSA level in the blood. If this remains stable, no further investigations are necessary. It is important to attend these check-ups regularly. They take place every three months in the first and second year after the end of treatment, every six months in the third and fourth year, then once a year.

Tags: hair stress organ systems

.jpg)