"Difficult when the personality fades"

All content is checked by medical journalists.Martina Rosenberg looked after her parents for eight years. The mother: Alzheimer's. The father: stroke. Her home has nothing to do with the multigenerational house of her dreams, and her parents' illness becomes an acid test

Frau Rosenberg, “Mother, when will you finally die?” Is the name of her book *, the title was your idea. Are you allowed to think that?

I understand that people who have not yet faced the issues of care, infirmity, grief and death are likely to react in horror. But when a person suffers and there is no longer any perspective for him, then it is a salvation if he is allowed to die. So it was for my mother, who had Alzheimer's disease. Sometimes death is the better alternative, and it has to be said in fairness - also for those around you. But it would be a shame if a mother felt addressed personally - I am also a mother.

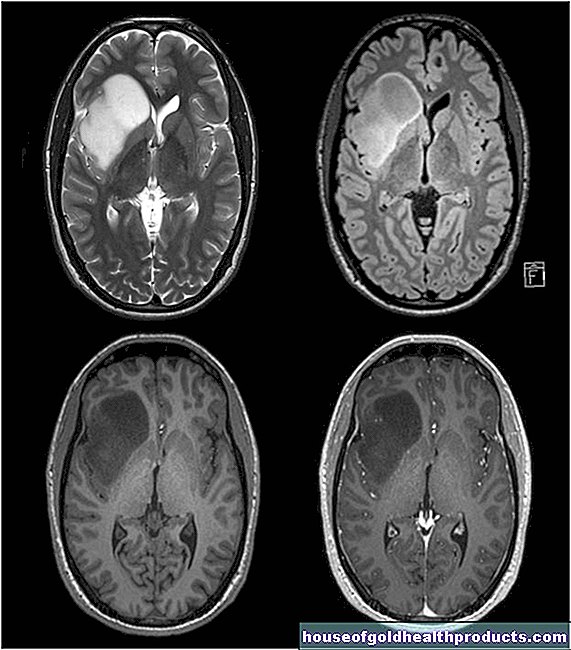

Your mother, a paragon of patience, a family man and mouthpiece for your father, fell ill with dementia - how has she changed?

She was more self-centered and more focused on her interests. That was unusual for her. Because my mother selflessly looked after the family all her life, especially my father. I found it terrible all these years, the way she had subordinated herself to my father - I'm rather the opposite. With the onset of dementia, she watched the television program she wanted. She drank coffee without bringing my father one first and no longer made breakfast every morning. I thought it was a late emancipation.

But it didn't stop there.

No, she gradually lost many skills, became highly depressed and suffered extremely from her fate. She no longer recognized the house in which she lived as hers. For example, she asked, 'Can we go home, please? I don't live here ‘. Like a broken record, she started over and over again. It annoyed and stressed my father, he just didn't understand what was going on in her. Besides, she could no longer articulate herself, she could no longer find the words in her head, and often said, 'What happens to me?' She was quite desperate about it.

You moved into your parents' house with your husband, child and dog. With the mother's illness, the family dynamic picked up speed. What happened?

My father probably lost attention when my mother got Alzheimer's. My parents were married for almost 60 years - he was always the focus of the family. When he was sick, the flag hung at half-mast. And when he had a cold, my mother carried the speed handkerchiefs after him. But suddenly she couldn't do that anymore. Many men of this generation have difficulty getting by on their own. They cannot cook and no longer know what to wear. So my father tried again and again to lead her back into the ‘real‘ life. He always had the hope that things could be the same as before. He could neither understand nor allow that the previous life was over and a new one had begun. He was unable to accept the events and his fate.

You were horrified at how rough your father was sometimes with your mother. You write that his behavior was “more than irritating”.

It is definitely difficult for everyone when the personality of someone close to you goes away like this. For example, my father was very upset that he could no longer communicate with her. 'Your mother talks nonsense all day, nobody can take it!' He scolded. And when she kept saying that she didn't live here at all, he put her in the wheelchair and said: 'I'm going to bring your mother home now.' Of course, I intervened. He didn't really understand what Alzheimer's meant.

Did you sympathize with your father?

I saw that he was on his nerve because it was incredibly exhausting with my mother. There was a period when she needed constant attention. She was hyperactive, but no longer as mobile. We couldn't do anything right all day, no matter what we tried. Even the carers were stressed. However, I did not understand why my father did not allow any help. I made a lot of suggestions to him, for example, to recover in rehab, to gain distance and to come to. But he really wanted to stay with his wife - even if that meant his downfall. They were like two drowning people clinging to each other - neither of them could swim.

Yes, you have to be able to say that honestly. With my mother I realized that it is not the look that makes a person, but the way they talk, the laugh, the gestures, the facial expressions. That is what you love and appreciate about a person. When that's gone, I find it very difficult to keep bringing up the feelings. You have to dig them out of the past. Maybe my father felt the same way.

Her father suffers a stroke and severe depression. Instead of living in a multigenerational house - your dream - you were suddenly living in a nursing home.

That's correct. I was only busy organizing things for my parents: visits to the doctor, correspondence with the health insurance company, banking, getting medication, shopping, instructing nurses. My parents couldn't be left alone for a minute. They were care levels 2 and 3. I slipped into it because I wanted to help. We siblings never sat down and thought about who should look after the parents. But I had the most intensive contact with them beforehand. I'm still a fan of multigenerational houses - old and young is a great combination if both make an effort.

Her parents never wanted to go to the home. Was caring an obligation for you as a good daughter?

My mother told me when I was 17 that a home was the worst thing you could do to her. She probably thought the people were not being properly cared for there. So my parents put the responsibility on me. But there are situations in which a home is a better choice. This is a difficult step because you take a person out of life and lock it up - it never comes back. My mother would definitely have been better off in a home where people with dementia are adequately dealt with. And my father might have lived nearby and so could have taken part in life a little again. But those were just my thoughts and wishes for both of them.

You did not receive thanks or appreciation from your parents for your commitment.

No not true. The thanks were just words. My parents took my commitment for granted, it was expected of me. They never reached out to me and said, 'Girls, if you can't do it anymore, we could try this or that.' My father was no longer able to consider other lives and people. He didn't care if I was sick either. I had tinnitus and high blood pressure. He just asked, 'Why weren't you there?'

The situation at home came to a head. Your mother's unrest, your father's terror, the dispute between the nurses - at some point you fled.

There have been many grueling situations. My father started campaigns to purposefully mess up my life. One day he got up at six o'clock, pulled up the shutters and woke my mother, who was restless and wanted to get out of bed. I had to work and didn't have time to put them on. The nurse didn't come until eight o'clock. That was a mess. My father was happy that I was finally there and that he could show me how many problems he was already having. It was then that I realized that that would never change as long as I lived in the house. He would try to drag me down with him. Perhaps subconsciously he wanted me to follow in my mother's footsteps. If he needs anything, I'll jump, but I wasn't ready for it. I looked for the distance to catch myself again.

How bad did you feel about leaving your parents behind?

It wasn't easy for me. I already had the feeling that I was going to let her down. But I tried everything and went to my limits. I even made a list of why I'm a good daughter. He would never have said: 'You do everything for us, and I try to behave in such a way that you can lead your life as best as possible.' They just let a roller roll over us all. So I actually think that my parents let me down.

Were there nice moments in the eight years of care?

No. As long as my mother was alive, I can't remember anything beautiful. There were good moments with my father when my mother died. Communication with him was more possible there. I often drank a glass of wine and talked to him. He was happy and a little more peaceful. I recognized him on those evenings.

After all, against the will of the family, you made the decision that your mother should be allowed to die. You write that you felt like you were killing your mother yourself.

I was definitely the driving force behind finally letting her die when she failed to recover from pneumonia. My siblings supported it, I couldn't involve my father at all, which was unimaginable for him. And the doctor told me factually that my mother would suffocate - of course that scared me. I was there during the entire dying process, but in between I was no longer sure that I had made the right decision. I didn't know what a dying person meant and how one could help him. I can't buy books first. I would have liked a doctor to be able to accompany a dying person and not leave it to the relatives alone.

They hoped for the death of their parents in order to be free. Has that come true?

Absolutely. My mother's death was a certain liberation because she was past suffering. She had left years ago, but I couldn't mourn her because she was still sitting there. It's like when someone is missing: you can't really say goodbye. When my father died nine months later, I was able to shape my life again. I was actually a new person.

You clearly said to your daughter: 'There is no way I want you to look after me.'

Yes, that has to be addressed. I want to grow old independently and make a decision when I am still mentally able to do so. Assisted living or homes, I can look at them beforehand, then the dilemma does not arise. I want my daughter to visit me only to see if I'm okay, take me on a trip or bake me a cake. Both should be happy that they have each other.

Ms. Rosenberg, thank you for talking to us.

Ingrid Müller conducted the interview.

Tags: menshealth palliative medicine Diseases