ESWL

All content is checked by medical journalists.The ESWL is a procedure for the treatment of urinary stones and gallstones. The term ESWL stands for “extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy” and describes the smashing of stones by sound waves that are generated with an energy source outside the body. Read everything about the ESWL process, when it is necessary and what risks it entails.

What is an ESWL?

ESWL, also known as extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, is a treatment option for gallstones or urinary stones. A transmitter placed on the skin transmits sound waves into the body, which break the stones - which can occur in the kidney or ureter, for example - into smaller pieces. These are then removed via a probe (endoscope) or eliminated by themselves. In this way, most urinary stones and gallstones can be treated successfully. Usually two or more sessions are necessary for this, whereby a maximum of three ESWL sessions should take place in a row. A session lasts approximately an hour, depending on the size and location of the stone.

When do you conduct an ESWL?

The ESWL is suitable for almost all stone problems. Primarily stones of the lower urinary tract are treated with it, i.e. kidney, ureter and bladder stones. Stones of the pancreas (pancreas stones) can also be smashed with the ESWL. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy is rarely used for gallstones because the stones often return after treatment.

The success of the ESWL depends, among other things, on the size, location and composition of the stone. The ESWL is well suited for smaller urinary stones of up to 20 millimeters in size.

An ESWL, on the other hand, may not be carried out in the case of:

- Bleeding disorders

- pregnancy

- Urinary tract infections

- Relocation of the urinary tract behind the stone

- Inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis)

- untreated high blood pressure

What do you do at an ESWL?

Before the ESWL, the patient is given pain reliever medication and, if desired, a sedative. In individual cases, treatment is also possible under general anesthesia. Antibiotic administration before ESWL is only recommended in patients whose stones have developed in connection with an infection.

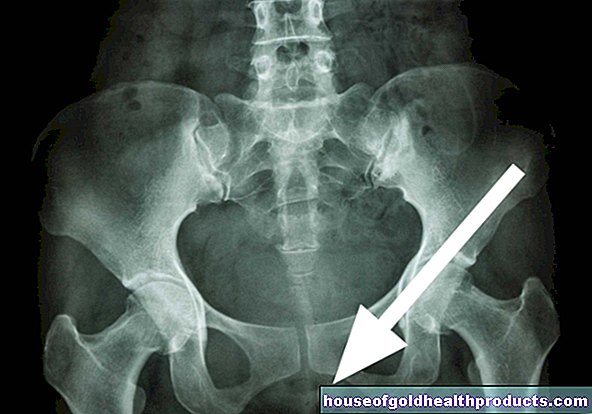

Stones of the lower urinary tract: ureter and kidney stone fragmentation

Urine is produced in the kidneys and drained into the bladder via the two ureters. From there, the urine is excreted through the urethra. The ureter, bladder and urethra are also summarized under the term "lower urinary tract". If stones form in this system, the doctor can perform an ESWL.

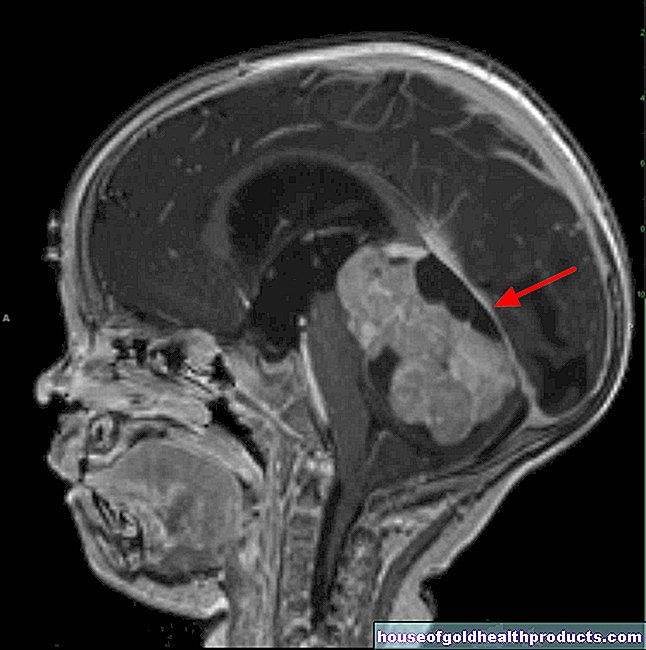

Once the doctor has determined the location of the stone in the ultrasound, he places a transmitter on the patient's skin and directs it towards the stone. With a frequency of 1.0 to 1.5 Hertz, the stone is bombarded with shock waves that are generated outside the body by a so-called generator. Due to the shock waves, tensile and shear forces act on the stone and shatter it.

In the case of larger urinary stones, the doctor places a splint (double J catheter, pigtail catheter) in the ureter so that the stone can be safely excreted with the urine.

Stones of the pancreas and bile ducts

Before pancreatic and gallstones can be treated, the doctor determines the exact location of the stones with the so-called ERCP (endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography). To do this, the doctor pushes a tube with a small camera over the mouth and small intestine of the patient, who is anesthetized and lying on their side, until the bile and pancreatic ducts are reached. He then injects a contrast agent into this so that the ducts are clearly visible in the X-ray image. Once the doctor has located the stones, the ESWL is finally used.

ERCP complications are rare, sometimes inflammation of the pancreas and bile ducts occurs. The tube can also injure the lining of the intestines and cause bleeding. The patient should fast for at least six hours prior to the ERCP examination.

According to the ESWL

After ESWL, urinary stones can be excreted in the urine via the urinary tract. The gallstone fragments also usually reach the outside via the intestine. Sometimes it becomes necessary to remove the stone pieces with a probe (endoscope).

What are the risks of an ESWL?

The following risks exist with ESWL, although serious problems with extracorporeal shock wave therapy rarely occur:

- Pain from the shock waves

- Cardiac arrhythmias during ESWL

- Increase in blood pressure (hypertension)

- Bruising in the kidney

- renewed increase in size of the stone pieces before excretion

- Colic when passing the stones

Crushed stones can also get stuck in the urinary tract or bile ducts again - urinary stones can cause urinary congestion, and in the worst case result in blood poisoning.

What do I have to consider after an ESWL?

The success of an ESWL can only be seen after six to twelve weeks during the ultrasound or X-ray control.

After urinary stones (ureter, bladder and kidney stone disintegration)

After a urinary stone ESWL you should drink enough (water, juice, tea) and exercise a lot. This will help ensure that the pieces of stone are washed out with the urine.

Since stone disease is always a symptom of an underlying disease, the doctor can often draw conclusions about the underlying disease based on its composition and treat it. So you should filter the urine for the ESWL and collect the stone fragments for analysis.

Stones of the gallbladder and bile ducts - litholysis

After the ESWL, the doctor can prescribe a drug that promotes the dissolution of the fragments (litholysis). With ursodeoxycholic acid you get a natural bile acid in tablet form, which you should take until the stone pieces dissolve.

Tags: Diseases foot care stress